| |

|

“Objects have the longest memories of all. Beneath their stillness, they are alive with all the terrors they have ever witnessed.” – Teju Cole, New York Times, 2014

I – Setting the Stage

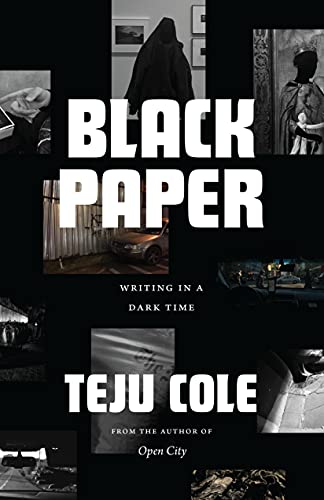

Teju Cole’s riveting new book of inspiring essays, Black Paper, published by the University of Chicago Press, is the latest gift from his fruitful and ever-accelerating career as one of our premiere culture critics. For several years he was the photography critic for The New York Times Sunday Magazine, a prestige posting from which he surveyed our world with sheer poetic clarity. Like many other people, one of the great joys in my life has been allotting a certain amount of time, variable depending on mood, to settling in for the duration needed to read the Sunday edition. Literally doing nothing for long enough to actually simply live, without any purpose at all other than traveling through the words and images elegantly and eloquently being presented in the frequently obscenely fat and multi-sectioned contents of the newspaper of record. Just lugging it home is enough to make me feel like I’ve won a survival contest whose reward is the pleasure of idleness for about two hours. The official word for this practice is, of course, reverie.

And each of us fortunate to be able to indulge in such relatively harmless pleasures has a certain strategic approach to reading it: how to begin, where to start, in what order, which section of which department, and so on. In my case, the first thing I separate out from the obese pile of newsprint (still such an analog joy in today’s gruesomely online digital world: news that actually comes off on your fingertips in vast dark smears) is the Sunday Magazine. There again, an opulent abundance awaits the reader, whether it be fashion, food or furniture. For me, it’s a seemingly humble little column in the up front section called “On Photography,” written by the breathtakingly gifted image maker and thinker Teju Cole. In my opinion, he is a national treasure. Unless you knew it was there, his regular column, which used the same name as a famous 1977 book of essays on photography by the great Susan Sontag, might be easy to glide right past in your search for end-of-week distraction. Once discovered, however, it was a must-see/read destination. It’s deceptively discreet presentation, generally a single quotidian image accompanied by about a page and a half of simmering type, also practiced a similar craft espoused by Sontag, that of ekphrasis, the poetic expression of emotive texts in direct personal response to works of visual art, in this case photographs.

His quietly poetic style was absolutely perfectly manifested to arrest the reader/viewer for far longer than you may have thought possible at first. The quote used above, for instance, has stayed with me on my writing desk for seven years and confronts me daily with an awareness that is nearly confounding in its emotive depths. The only other writers capable of achieving that kind of utter resistance to absorption are perhaps different in each of our lives, W.G Sebold and David Foster Wallace in mine, for instance, but the skilled surfing of the meanings hiding inside things is a shared ability you have to have been born with. Cole is so accomplished in both his chosen arts, images and words, that he’s overwhelming in a kind of shy and almost retiring, reticent way (he is what my late father used to call ‘scary brilliant’) and also so seductive that once you know he was there, embedded amongst the early ads in the magazine like a simmering bomb of beauty, you started to explore his other means of expression and find to your astonishment that he has also exhibited his own photographs with drastic success and written reflections on being absolutely alive in repeated forays into published essays that have created a formidable edifice.

Scary brilliant, and it is rare for a practitioner of an art such as fabricating the frozen music of images to also be so singularly adept at being a culture critic who can so fluidly explore the beauties or terrors of his peer photographers that one feels invited into a secret cult of sorts: the place where the rituals of aesthetic aura are being celebrated in ways that also bring us perilously close to actually understanding the meaning of such terms as affect, the power of emotional impact in action, and agency, the power of taking action in the world based on privately cultivated propulsion. Alas, Cole was the photography critic for The New York Times Magazine only from 2015 to 2019, and I’ve missed him every Sunday since. But he’s also, fortunately for me and his other followers, been very busy elsewhere, and now has the extra time away from a weekly column to exhibit his own work as well as dive deeper into our visual culture as an astute assessor of our precarious life in the 21st century.

In a review in Feature Shoot Magazine of a Cole solo exhibit, the critic Miss Rosen observed with an acute eye and mind just what makes him so special for so many of us:

The relationship between image and text is one of the most challenging pairings to exist. They demand complete attention and so one must choose: to look or to read—and in what order? Perhaps it seems deceptively simple: one simply does as they are inclined. Yet regardless of preference, they inform each other, infinitely. When we read, we see the picture in our mind. When we look, we write the words ourselves. Now we are asked to forgo our imagination and focus on the given context. Yet few can bridge the gap that exists between the linguistic and visual realms, the distinctive forms of intelligence that operate independently and interdependently at the same time. Most often, we simply opt out somewhere along the line, wanting to return to the freedom to imagine for ourselves rather than listen to what we are told. Writer Teju Cole understands this well. As photography critic for The New York Times Magazine, Cole mastered the painting of pictures with words that illuminate and elucidate in equal part, so that his words both add and peel back layers from that which appears before our eyes.

In his first solo show in 2017, Blind Spot and Black Paper, at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, the writer brought us along for a journey around the world, looking at life not only through his eyes but experiencing it through his prose. The exhibition, which accompanied the publication of his fourth book, featured a selection of 30 color photographs accompanied by a single paragraph. Each piece of text is a beautifully encapsulated prose poem that draws us into uncharted depths, giving voice to the image that quietly beckons us with its simple, subtle lyricism of color, shape, and form.

And that insight of his into the stillness of objects and their memory that so impacted me, with places actually being just bigger objects, is richly evident in many of his ekphrastic experiments, as demonstrated so well when we travel through some of his powerful images and evocative words.

|

| Brienzerzee, from Fernweh (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY) |

I opened my eyes. What lay before me looked like the sound of the alphorn at the beginning of the final movement of Brahms’s First Symphony. This was the sound, this was the sound I saw.

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh, (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY) |

Stillness. In the interior, she reads with lowered eyes, unaware of what comes next. A presence made of absence.

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh (2015, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY). |

I sat there for hours and watched the sun slip across the landscape. Anything can happen. The point is to shatter serenity; the absurdity of contrast between before and after is the very point

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY). |

You take around 7500 steps each day. If you live to eighty, that comes to 200 million steps over the course of your life, a hundred thousand miles. You don’t consider yourself a great walker, but you will have circumnavigated the globe on foot four times over.

II – Staging the Play

Teju Cole is as versatile as he is prolific. A novelist, photographer, critic, curator and the author of seven tantalizing books, among them Open City, Blind Spot, Golden Apple of the Sun, Fernweh, and his latest one, Black Paper, he was a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow, and is currently the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard. Based on even that snapshot of his résumé, and my reading of his ruminations over the course of many rewarding years, one thing I know for certain is that it is virtually impossible for Professor Cole to teach any other living human being how to write the way he does. His style is so graceful, elliptical, digressive, entertaining and educational, even or especially for the average lay reader, that I’m pretty sure all his lucky students can really do is keep their mouths shut and hope to somehow soak up some of his splendour, perhaps by osmosis. And Black Paper feels like a little way station in a snowy niche on the way to the top of a mountain range where spookily gifted writers such as Walter Benjamin or Harold Rosenberg go on vacation. It is also almost a work of theatre, not because it is in any way theatrical, but rather because the scope of its sweep, into and out of a vertiginous array of subjects and themes, has an epic-tragedy kind of vibe about it.

Characterizing him as “a kind of realm” in The New York Review of Books, Norman Rush summed up Cole’s mission quite nicely: “Teju Cole is an emissary for our best selves. He is sampling himself for our benefit, hoping for enlightenment and seeking to provide pleasure to us through art.” The key notion here is that of sampling, usually a musical term for collaging different fragments of different musical sources into a unified score, frequently one with a hip-hop flavour. That active aspect of mixing, matching and merging is precisely what Cole does in most of his works, whether on images or on social and cultural issues, and especially as conducted in Black Paper, perhaps the most far-ranging, diverse and multi-faceted sampling of his acutely aware experiences of our postmodern world yet.

His bicultural origins – he was born in America in 1975, raised in Nigeria until he was 17 and brought back to America with his family to study art and then medicine, before returning abroad to study African art history and Northern Renaissance art at Columbia U. in New York, serving as writer-in-residence at Bard College and writing a flurry of novels – have all accumulated the perfect amount of intellectual gravitas and cosmopolitan charm to gracefully, i.e., effortlessly, startle us with a truly polyglot stew of knowledge. He stirs this dreamy stew ideally in Black Paper, where he declares, “Darkness is not empty.” as he proceeds to navigate his way through a variety of meditations on what it means to maintain our humanity in a time of darkness. One solution, he has suggested here, is to be intensely attentive to our experience, so much so that it’s not so much about seeing what’s going on, to take it all in, but also to consider what it is we’re not seeing and what is not happening, but which should be.

The essays in this new collection, ranging across five separate parts, commencing with a masterful consideration about what makes the Italian painter Caravaggio so important, through territories he calls “Elegies” (containing great insights into the image historian John Berger and cultural historian Edward Said), “Shadows” (containing clear glimpses into the work of artists Kerry James Marshall and Lorna Simpson), “Coming to Our Senses” (with skillfully clarifying approaches to ethics) “In a Dark Time” (with touching portraits of refusal, resistance, and cooperative living) and “Epilogue: Black Paper” (a stirring counterpoint to Caravaggio which abstractly explores the links between literature and activism while still remaining a deeply humanist document). Along the way, he also manages to make manifest the power of the colour black in the visual arts and the role of the shadow in photography. The last section also contains one of the most heart-wrenchingly simple observations about our shared harrowing time that I’ve read in ages: “An incalculable number of people cried themselves to sleep in those days.”

What’s a premiere photography critic doing writing about the painting of Caravaggio, you might well ask? Well, first of all, Cole is so eloquent that he could write about the history sheep farm fences and make it transformative and compelling, and after all, the subtitle of his new book is Writing in a Dark Time, which brings us to Caravaggio in the most logical of ways. Caravaggio, apart from leading a tragic life, dying young, influencing every painter after him, and in the cauldron of his own feverish brain practically inventing the Baroque style in art, was utterly immersive in a manner consistent with our present era. He was also among the first exponents of complete subjectivity in art, one of the hallmarks of our own age, and he skillfully indulged his own private obsessions practically to the exclusion of all else. Most importantly, perhaps, Caravaggio was photography. For the roughly 250 years from Caravaggio to the French invention of the camera in about 1840, his representational style was the main means of producing mimetic memorials to actuality.

Cole, an accomplished novelist as well as essayist, not only knows this but also acts upon it, by bookending his approach to Caravaggio with his appreciation of a contemporary such as Lorna Simpson, an American conceptual photographer and multimedia artist whose radical works on paper extended the exploration of representation, identity and history. In some strange ways, apart from the shift from painting to photography, she is examining the edges of perception in precisely the same way that Caravaggio did. Cole also reminds us of what the novelist Mary Gaitskill stressed so well: “Fiction is to literal representation what painting is to photography: it’s just not claiming to be ‘real’ in the same way at all.” And it is precisely because Cole himself blurs the arbitrary lines between fiction, essay, poem, elegy, document, social activist, artist and critic that he is able to stride so confidently across the landscape of subjects and themes in this new book. He thus approaches the drastically fractured moment in history we currently occupy via a stunning constellation strategy: discussing the confrontation with the parallel arcs of unsettling art in unsettling times from every possible angle.

Unsettling, yes. Here is why we need to nourish ourselves on Cole’s proteins, whose own images are strong but whose words are even stronger, once again reflecting on the traveling vitamin called Caravaggio:

Porto Ercole was the final unanticipated stop. He’s buried somewhere there. But his real body can be said to be elsewhere: the body, that is, of his painterly achievement. He was a murderer, a slaveholder, a terror and a pest. But I don’t go to Caravaggio to be reminded of how good people are, and certainly not because of how good he was. To the contrary: I seek him out for a certain kind of otherwise unbearable knowledge. Here was an artist who depicted fruit in its ripeness and at the moment it has begun to rot, an artist who painted flesh at its most delicately seductive and its most grievously injured. I don’t have to know him to know that I need to know what he knows, the knowledge that hums, centuries later, on the surface of his paintings, knowledge of all the pain. Loneliness, beauty, fear and awful vulnerability our bodies have in common.

|

| Caravaggio, Flagellation of Christ (1607, Naples). |

See what I mean? Our own weird time often seems as dark of Caravaggio’s time was, which is why he still matters, since he seems to know us almost more than we know ourselves, and even at least as much as a contemporary artist such Kerry James Marshall does. They are both, as Cole so deftly demonstrates, about repentance, atonement, reconciliation and redemption. Caravaggio knew he needed to repent, in fact he was repenting almost every twenty minutes, and he especially repented in each painting, while Marshall masterfully reminds us, especially white culture, that it is high time for the rest of us to repent as well. In a hundred years, if there were to still exist an archive of memory such as the famed Encyclopedia Britannica, and that’s a big if, one can easily imagine a single entry capable of adequately covering and capturing the strange years between 2020 and 2022. And that entry would have been written by Teju Cole in Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time:

Many fell ill, illnesses that showed on the face and illnesses that didn’t. We knew and we didn’t know. Poverty began to burrow into those lives. Shame made a home in some people, some went hungry, hunger hollowed them out. The stock market was up, but many pockets were empty.

– Donald Brackett is a Vancouver-based popular culture journalist and curator who writes about music, art and films. He has been the Executive Director of both the Professional Art Dealers Association of Canada and The Ontario Association of Art Galleries. He is the author of the recent book Back to Black: Amy Winehouse’s Only Masterpiece (Backbeat Books, 2016). In addition to numerous essays, articles and radio broadcasts, he is also the author of two books on creative collaboration in pop music: Fleetwood Mac: 40 Years of Creative Chaos, 2007, and Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, 2008, as well as the biographies Long Slow Train: The Soul Music of Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, 2018, and Tumult!: The Incredible Life and Music of Tina Turner, 2020. His latest work in progress is a new book on the life and art of the enigmatic Yoko Ono, due out in early 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment