|

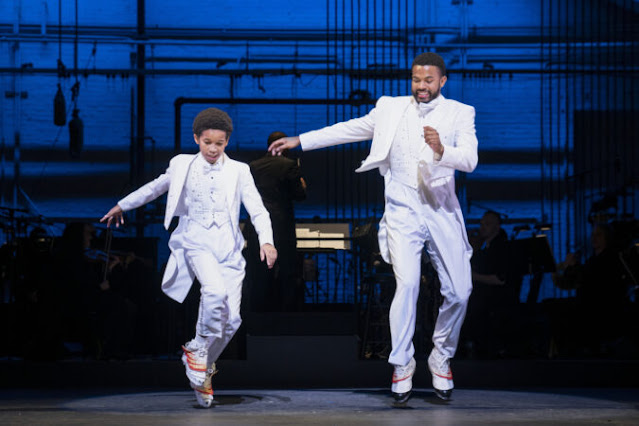

| Alexander Bello and Trevor Jackson in The Tap Dance Kid. (Photo: Joan Marcus) |

The return of the Encores! series to City Center over the weekend after two years in hiatus was eagerly anticipated, but the occasion – a revival of the 1983 musical The Tap Dance Kid – turned out to be dispiriting. To start with, the show, which I missed the first time out, isn’t very good. Charles Blackwell’s book (based on a novel by Louise Fitzhugh – of Harriet the Spy fame – called Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change) is a retread of the antique melodramatic plot about the boy who has to fight his stiff-backed father’s bias against show business to follow in his dancer-choreographer uncle’s footsteps and dance his heart out on the stage. Here he’s a ten-year-old Black kid from the Buffalo suburbs named Willie (played by the personable Alexander Bello) whose mother, Ginnie (Adrienne Walker), danced with her kid brother Dipsey (Trevor Jackson) and their gifted father when they were children. Ginnie raised Dipsey in cheap hotels on the road and took care of him when Daddy Bates went on benders. Then she married William (Joshua Henry), an ambitious lawyer who promised her a safe, respectable life. He delivered, but his vision of family life and of what bringing glory to the race is highly restrictive. He’s suiting up his son, who is bored in school but deliriously happy when he’s taking tap lessons from his uncle, for a career in law, while his teenage daughter Emma (Shahadi Wright Joseph), a bright young woman who covets that career for herself, can do nothing to gain his approval. He’s not interested in Emma; she’s only a girl. And he bullies his wife, silencing her objections and making jokes about the troublesome women in this family. When Willie’s bad grades provoke his father into taking away his tap shoes and banning Dipsey from his home, the boy runs away to his uncle, who’s rehearsing a musical downtown that he hopes will be his ticket to Broadway. What it needs to succeed, in case you haven’t guessed, is a talented tap dance kid.

The script is clumsy and cramped, and the story line is about as plausible as a Busby Berkeley backstage musical film from the thirties, though we’re supposed to accept it on some level as gritty realism. The characters are barely fleshed in; Dipsey’s girlfriend, Carole (Tracee Beazer), isn’t even a sketch. I have no idea what Fitzhugh’s book might be like, but the narrative of the musical feels like it was written during rehearsal. And the songs by Henry Krieger (Dreamgirls, Side Show) and Robert Lorick are mostly dully familiar. (The two that end the first act, the up-tempo “Fabulous Feet” and the ballad “Man in the Moon,” aren’t bad.) The Tap Dance Kid exists as a showcase for tap numbers, and though there aren’t nearly enough of them in Kenny Leon’s revival, choreographed by Jared Grimes, they’re indisputably the high points, especially when DeWitt Fleming shows up as the ghost of Daddy Bates to partner young Alexander Bello on “Dance If It Makes You Happy” and when Bello and Jackson make their final appearance in white tuxedos, stepping high.

I know that Encores! productions are thrown together very fast, but The Tap Dance Kid is really, really sloppy. The singing is fine but much of the acting is sub-par, especially Jackson’s, and Dede Ayite’s costumes are so scrappy and uninspired that it would have been better if she’d simply put the actors in work clothes. Leon has barely staged the dialogue. The veteran Derek McLane is listed as scenic designer, but I’m not sure what he could have contributed. The playwright Lydia R. Diamond, who wrote Stick Fly and the witty race comedy Smart People, has adapted the book, moving it out of the early eighties back to the mid-fifties. But either she didn’t notice that she’d left in Emma’s reference to the 1967 movie In the Heat of the Night or it was someone’s not-so-clever idea to throw in a nod to the recently deceased Sidney Poitier; the anachronism operates like a flat tire. Emma tries (and fails) to persuade her father that it’s OK for a high school girl to show up to class in slacks rather than a dress; didn’t he spot her corn rows? Maybe there’s a time machine out back in the garage.

Joshua Henry, so good in The Scottsboro Boys and Violet and Shuffle Along, is stuck here with an impossible role. William is a bully with a load of prejudices; he’s in the musical partly as a plot device so Willie can have an obstacle to get over and partly so we can have someone to despise. Yet he’s the character who’s handed the big dramatic number just before the finale, “William’s Song,” in which he articulates his reasons for finding tap dance demeaning to Black people. In 1983 it hadn’t yet become politically incorrect to love a genre of dance that people of color performed for white theatregoers; now, when a Black man protests against it and executes a bitter burlesque of tap that links it to bowing and scraping, he’s sure to prompt cheers and applause from members of the audience, especially when a strong performer like Henry throws himself into it. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to Leon that Henry’s over-the-top 2022 rendition of the song (which made me cringe) is a stark contradiction to the character he’s been playing all evening. While he’s singing, the other principal actors, who are all on stage at the time, stand immobile; what else are they supposed to do, when they’re stuck in a collision between two warring impulses? Then they march into the wings, and the musical limps to its bizarre ending, where William abruptly realizes how badly he’s behaved toward his family, reconciles with each of them and gives his permission for his son to appear in Dipsey’s show. This is one of the oddest moments I’ve ever seen in a musical; I was embarrassed for everyone. The finale, where Jackson and Bello do their best dancing, isn’t just satisfying; it’s a reprieve.

– Steve Vineberg

is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the

Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and

film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review and is the author of

three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

– Steve Vineberg

is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the

Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and

film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review and is the author of

three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

No comments:

Post a Comment