|

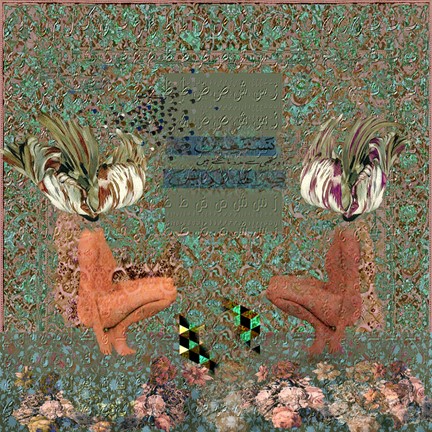

| Red Army II, 2022 digital print on metal, 48 x 48 inches. |

1. Singularity“Art ceases to be solely a form of self-expression alone in the electronic age. Indeed, it becomes a necessary kind of shared research and of internal probing.” – Marshall McLuhan, Through the Vanishing Point: Space in Poetry and Painting (1968).

The powerfully evocative and resonant works of Fatima Jamil are encountered by the entranced viewer as a truly nuanced hybrid of Eastern and Western traditions. In fact, it strikes me that they reveal a salient truth about the artistic urge to make images and our human appetite to absorb them into our nervous systems as a kind of remedy to the stresses of everyday living: the fact that there is no East or West in the immersive dimension of dreams. I instinctively refer to her otherworldly visions as icons, but not in the liturgical and canonical sense of that word, rather in the neutral sense of being iconic: a picture, image or other representation residing in analogy. She is also a visual storyteller par excellence.

True, icons can reference something sacred, and some aspects of her iconography do reference her cultural roots in Pakistan prior to moving first to Canada and then to California, where she currently resides and works in Orange County’s Irvine, relatively close to the bustling hub of Los Angeles. However, in semiotics, the icon is any sign that evokes resemblance, and in digital technology, which Jamil has readily embraced as an artistic practice parallel to that of her paintings and drawings, the icon is a picture or symbol that appears on a screen and is used to represent a file or application. The exotic media relationship between a textile canvas or wood panel, such as those customarily used in paintings, and the flickering electronic screen which serves as the basic foundation for most digital delivery systems, is rendered both subtly and poetically in her hauntingly otherworldly works. The origin of the icon identifier was first recorded in the 16th century (from Latin icon and Greek eikon, meaning likeness, image, or figure) and that century was also the stage for a vital arising of religious icons in the west, especially in Slavic cultures, and social icons in the east, most notably in the Mughal style prevalent in Jamil’s homeland prior to its being partitioned into India and Pakistan.

However, even though her work is not programmatic, in that it serves no liturgical or devotional function, it is nevertheless strongly ritualistic in the formal and aesthetic senses. She delves into a dream world which is at once both personal, reflecting many of her own insights into her cultural heritage, and archetypal, exploring many of our symbols embedded in what Jung called the collective unconscious of our species. She thus further unifies the polarities inherent in East/West dichotomies through her utilizing of digital technology in the formulation of her alluring visual narratives. Narrative, in its most immediate, ancient and yet effectively postmodern format, is her graceful gift to us, especially when the hero is a heroine.

|

| St Nicholas of Myra, icon (15th century). (British Museum) |

|

| Mughal miniature by Govardhan, ca 1620. (Musee Guimet, Paris) |

In the body of her work, the female portrait is often employed, as well as the female figure, and this narrative element frequently takes the shape of examining traditional styles of representation delivered in a profoundly contemporary, even a futuristic, manner. Often a balanced duality is offered to the viewer that conveys both equilibrium and asymmetry at the same time. As the artist clarifies her interests:

The 'twins' essentially are for me polarities of experiences undergone by the same individual. In Two Mehndi Girls, there is fragmentation of the same verse, lower part is an Arabic verse from the Quran: sirat-al-mustaqim refers to the middle way, to the straight path in the Islamic context [sic]. The top line is the 'Nastaeen' translation: we ask for help. I am not sure how the fundamentalists would take this, first the nudity and second the fragmentation of verses from the Quran, not delivered in their entirety.

But, as Jamil further explains:

Art for me is a visual dialogue and should not be restrained or constrained in any manner. My art is not about those literal or textual aspects. Instead it is mainly derived from the narrative of being a woman and through the lens of the female gender. I also like the idea of the simulacrum, a simulation which does not necessarily literally represent what it shows. My imagery provides substitutes for the approximation of real events or even of no reality at all. I am neither concealing the truth nor representing it as a solid concept, since every truth is plural, and they have multiple variables which are not specifically fixed to a single idea. This commentary is thus culturally loaded with specific gender issues and with the many social expectations accompanying the realities of being a woman.

Jamil’s use of the traditional Mehndi motif in this multivalent and modern manner is equally radical. Mehndi is a temporary tattooing technique devoted to beautification of the bride with design patterns and is historically an integral part of her bridal identity. For Jamil to utilize it in a non-traditional, secular and abstract language is already somewhat experimental. It is derived from the Hindu culture and its traditions, emerging in antiquity from the epoch when India and Pakistan were one single country. Her motifs are often of gender, binary and non-binary.

For Jamil, an avowed secular feminist, this ancient motif is totally customary rather than religious: one of the oldest forms of body art which is generally used as an overall good omen for significant occasions. In her captivating and visually gorgeous works, she has used Mehndi in a truly modern manner, symbolizing the new-found identities for girls and women in their own right, not one relying on a man's role in their lives or his dominant importance as a justification for adorning themselves.

|

| Two Mehndi Girls (2022), digital archival print, 30 x 30 inches. |

As a young girl, and later as an art student, Jamil was inspired by the intensity of the manga style of Japanese art, as well as comic books (aka graphic novels), typographical lettering, dolls and puppets, all of which have mysteriously found their way into the highly formalized and idiosyncratic styles employed in her recent works. This is especially the case in those works that demonstrate an affinity for iconic representations of feminine faces, such as her mysterious twins and metaphorical doll heads, or the silhouette and cameo form of portraiture she often employs. Her work is about building bridges between polarities, especially those dualities of gender roles and interactions.

Subsequent to her move to California to pursue her Masters of Fine Art at California State University in 2006, where she was also an instructor, she began studying digital design at Otis College in Los Angeles. During a hiatus between art-making projects, she did a great deal of private research and active exploration of her personal ideas, poetry and alternative avenues to experiment with aesthetic production in ever more complex formats. Since she greatly enjoyed traditional printmaking, she also started to experiment with digital art as a corollary medium, where she found that the immediacy of drawing and painting, via the building up of multiple layers, was quite similar to the techniques she had used earlier in the more traditional methodologies of prints.

But electronic brushes: this fresh digital technology, and its somewhat limitless visual dimensions, also merged with mixed-media forms, further permitted her to embrace a new-found freedom of expression, and perhaps was a means of exploring her interests in formats far afield from her original set of training skills. She also then branched out to the media of film and ceramics, and is currently working on creating digital effects in moving imagery, as well as the making of large sculptural ceramic heads. These new works in progress are at present being refined for an upcoming solo exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art.

|

| Twins and the Watermelon Moon, an unsettling set of dual icons (2022), digital mixed media, 40 x 60 inches. |

2. Epistrophy

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .” – Walter Benjamin, ca 1930.

Once artists such as Fatima Jamil, already entranced by the optical unconscious of their own heritage, embraced the digital age we now occupy, they found themselves in a vast unexplored wilderness overflowing with resources capable of sustaining a new kind of aesthetic exploration. As McLuhan had so presciently pointed out, in the electronic age art ceased to be solely about the individual self and instead evolved into an internal probing of the collective mind. That mind is an open pasture for artists such as Jamil. Another visionary, the astute culture critic Walter Benjamin, had also examined the power of images and the meaning of their transmission in his masterful study of the poetics of reproduction. Digital imagery gives Jamil a means of multiplying her dream layers even further and creating a community of wonderment for all of us to visit. Indeed, we already live there, in a place Benjamin predicted so long ago: a magical digital country where every copy is also the original.

|

| Nirvana One, new media on metal, 30 x 40 inches. |

|

| Nirvana Two, new media on metal, 40 x 40 inches. |

|

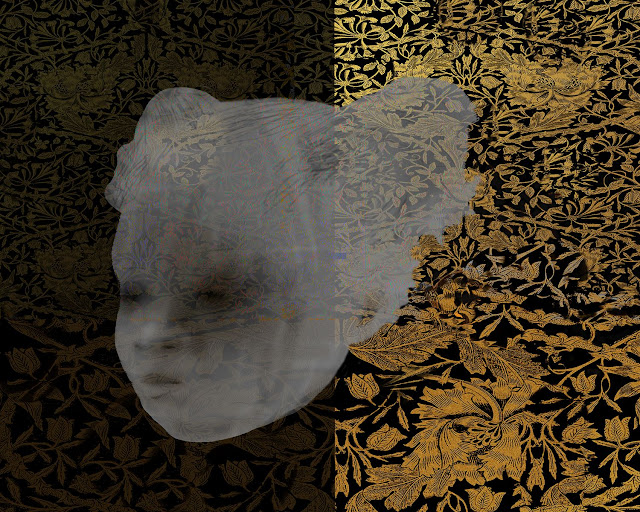

| The Veil (Emergence), ink on paper, 40 x 60 inches. |

The recurring girls’ heads and metaphorical dolls, presented often in profile and in shadow, are examples of this motif, as in The Veil series, which are often offered hovering mysteriously before crisp and active graphic patterns. In the case of this artist’s representation of a profound phenomenological femininity, she approaches the expressionless almost immediately and lets the viewer rest there. With the expressionless, by the way, Benjamin was referring not to being without any expression but rather to entering the very edge of what can be expressed at all. It was this point, he posited, that the full ‘meaning-value’ of a work erupted in the form of its visual aura, a certain kind of emotional distance which does not decrease the closer we get to a work but rather expands perpetually.

Benjamin also conjectured that the aura of a work of art undergoes a kind of diminishment or decay upon its reproduction in print (as explored in his famous 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”) and that only the original ritualized work can have its authentic aura. But since he passed away in 1940, he was unaware of the domain we now all take for granted, the electronic age and the digital realm, the place where, as I’ve suggested, every copy is also the original. In this regard, his work was in a sense taken up by the next visionary of the aura, Marshall McLuhan, whose entire body of work was a prophetic forecasting of our electric age and even of the internet itself.

Thus we have long been in need of an updated version of Benjamin, one which appreciates the work of art in the age of digital reproduction, and that is what I believe McLuhan’s thinking offers us. McLuhan, who passed away in 1980, just prior to the arrival of personal computers and desktop studios, would, I believe, have had a field day with many of the most compelling iconic images of Fatima Jamil. Especially perhaps the ones printed on thin sheets of aluminum, thus approximating a tactile kind of screen, in addition to the equally arresting ones committed to ink on archival paper.

However, one of the principal examples of the Jamil aesthetic methodology, and for me one of the most compelling, captivating and downright alluring pieces I’ve ever encountered, is still a C-Print, inherently a very sophisticated and tonally saturated photograph, a historical technology which first emerged in France way back in 1840. Obscurity of the Glowing Beam, with its sparse mindscape and hovering pony-tailed icon, is a masterful meditation on both life and mortality, on being earthbound but also transcendent, and it conveys once more the feeling of an embodied meaning, one almost as evocatively tender as frozen and melting music.

|

| Obscurity of the Glowing Beam, C-Print, 40 x 40 inches. |

Almost as a counterpoint to the solitary hovering specter in the sedate Obscurity of the Glowing Beam, the multitude of proliferating red dolls’ heads, or pony-tailed girl’s portraits, swarming in the somehow still peaceful terrain of actively dancing arabesque cube designs arrayed in Red Army II, paradoxically induces in the viewer a placid state of calm surrender. While still a spectral dance, this richly patterned ballet of heads, which almost feels like an embroidered texture of cloud forms, seems to invite the flock of floating red heads to enter a magical beehive of repose, where perhaps all our racing thoughts eventually come to rest. Red Army is among the most arresting of Jamil’s icons, and yet it has an alluringly peaceful heart beating in its robust center.

There is however, a restlessness at the heart of every great artist. The truly creative maker of visual stories really is a slave to risk, in the most positive sense of that phrase. Once they have achieved their objectives in one visual language they seem to shift gears almost immediately and take us on a wild ride into another one. We are the fortunate beneficiaries of their apparently endless appetite for risk, and so it is with Jamil. Having elaborated a veritable encyclopedia of emotions associated with the feminine dreamworld through her drawings, paintings and digital compositions on canvas, paper and metal, she is currently embarking on yet another expedition into the unknown, into terra incognita, a place on no maps.

And in the end, perhaps the most amazing thing about this otherworld that her accomplished work so skillfully unveils for us is that it was right in front of us, staring us in the face, the whole time. Now, it’s our turn to return its intense and poetic gaze.

No comments:

Post a Comment