|

| (W.W. Norton Press) |

“The Beatles, like Duke Ellington, are virtually unclassifiable musicians.” – Lillian Ross, writing in The New Yorker in 1967.

How can one possibly explain the majestic presence of music such as Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life” and “Chelsea Bridge”? Or the shimmering beauty of Lennon/McCartney’s “She’s Leaving Home” and their entire “Abbey Road Medley”? What secret alchemical equation is behind the binary Odd Couple Code in the creative arts that makes such great collaborations so fruitful? A team of rivals, often incompatible and yet somehow incomparable, whose rivalry makes the team grow stronger and succeed far in excess of what either competitive team member could achieve alone, is an often mystifying but vastly entertaining cultural phenomenon. As long as they maintain the precarious balance required to equally channel their dramatically opposite energies in the same direction, that is.

Help!: The Beatles, Duke Ellington and the Magic of Collaboration, the wonderful book by Thomas Brothers from W.W. Norton, is one of the most informative and inspiring places to begin examining this remarkable ability for two artists to meld into a unified field, a single creative force in tandem. The odd-couple metaphor of a relational golden mean suggests something hidden but potentially profound, something we could even call reciprocal maintenance. This arrangement of forces basically requires both partners to take turns, maybe even alternate, at being the dominant prevailing portion of the whole, pivoting frequently to allow the opposite partner to assume the same majority role as often as possible.

In other words, to trade off being the small part relating to the large part (the individual) in the same ratio as the large part is to the whole (the collaboration). How can we plumb the breathtaking harmony that often results from intensely intimate and competitive accord? Among the greatest examples are the collaborations of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, in addition to the spectacularly gifted producer George Martin’s partnership with The Beatles as a structural unit, which reveals the central role he played in making their music what it was and still is. The other collision of talents in popular music to carefully consider, this time in the jazz idiom, is that of the great pianist and composer Duke Ellington with his longtime songwriting partner and arranger, the genius prodigy Billy Strayhorn. This task is undertaken with considerable aplomb and zeal in this important Brothers study.

Reflecting on the collaborative origins of some of our greatest music, to explore their mutual blueprints, so to speak, from “Mood Indigo” and “Take the A Train” to all of Rubber Soul and Revolver, can often clarify how such amazing compositional achievements occupy the landscape of both our culture and our own personal experience. So here we might attempt to imagine the collaborative biographies of their double-barreled ancestries in all our lives. True, writing about music, as the inimitable Elvis Costello once remarked with typical sarcastic bravado, might be like dancing about architecture, but it is equally true that some architecture deserves to be danced to. Especially when it’s as otherworldly as both Duke’s and the Beatles.

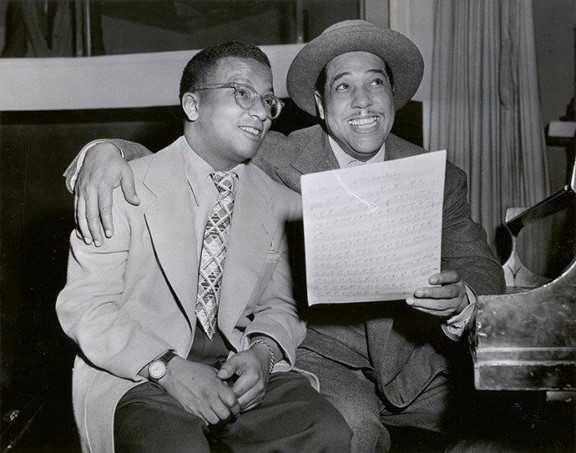

|

| Duke with his songwriter/arranger, the brilliant Billy. (Ellington Society) |

The same can be said of the most popular British or American songwriters and band arrangers of the first half of the twentieth century, those who tended to work in teams: the Gershwin brothers, Rodgers and Hart, and various lyricists with composers such as Kern, Arlen and Ellington. Every shadowy mirror, working within the tightly controlled confines of a partnership game we might call double solitaire, reflects a story, and sometimes, on rare occasions, the resulting work they make together as a team reaches almost unheard of heights. Such was the rarefied atmosphere achieved by the talented subjects of this Brothers tome, examining a contribution to cultural sophistication which has rarely been even approximately matched.

As a kind of preamble to this lofty realm of mutual muses, a glimpse into the dynamics of creative collaboration is a useful place to start. According to Vera John-Steiner in her book Creative Collaboration, all of us have been held in the thrall of an illusory cultural assumption:

Rodin’s famous sculpture, ‘The Thinker’, dominates our collective imagination as the purest representation of human inquiry, the lone, stoic thinker. Yet while the western belief in individualism romanticizes this perception of the solitary creative process, the reality is that artistic forms usually emerge from the joint thinking, passionate conversations, emotional connections and shared struggles common in all meaningful relationships. Many of these collaborators complemented each other in major ways, meshing different backgrounds and forms into fresh styles of thinking, while others completely transformed their respective fields.

John-Steiner illustrated that the creative mind, rather than thriving on solitude, as we customarily but erroneously imagine, is clearly dependent upon the reflection, renewal and trust inherent in sustained human and professional relationships. Such compelling depictions demonstrate the key associations that nurtured all our most talented artists and thinkers. While compelling, the creative alliances she studied are generally synchronized and synergistic, where supportive compromise reigns. What motivates such extended collaboration is generally some deep compatibility, though what is equally intriguing is the coupling of certain successful creative ensembles who are woefully, utterly, and entertainingly incompatible.

We need to unearth the quantum level of creative partnership itself, and that means finding the basic foundational level at which point these different sets of creative partners intersect, as do all the shared compulsions of their inherent creative pathology which they have in common. In my book Dark Mirror, I called the Beatles “The Seduction Shouters,” marveling at how they used each other as emotional windows through which to arrive at the breathtaking Mount Olympus of pop and rock music that they scaled. Their music was a seduction aimed at a world in need of a new affair of the heart. But paradoxically their seduction had to be shouted at a mass audience which was often louder than the original sung message itself.

Those wishing to understand the curious frenzy swirling around them would do well to pick up a fascinating little book by Nobel Prize-winning author Elias Canetti. In Crowds and Power, he abundantly explained the organic and unconscious nature of the relationship between the desires of crowds on the very precarious verge of becoming mobs, and the power of those artists, in this case entertainers, who are in the eye of the storm and are engulfed by the appetites of an abstract mind multiplied by thousands, even millions. In the case of Ellington and Strayhorn, and equally as marvelous in the orchestral jazz realm they mastered together, we have a bold variation which we might as well call “The Romance Whisperers.”

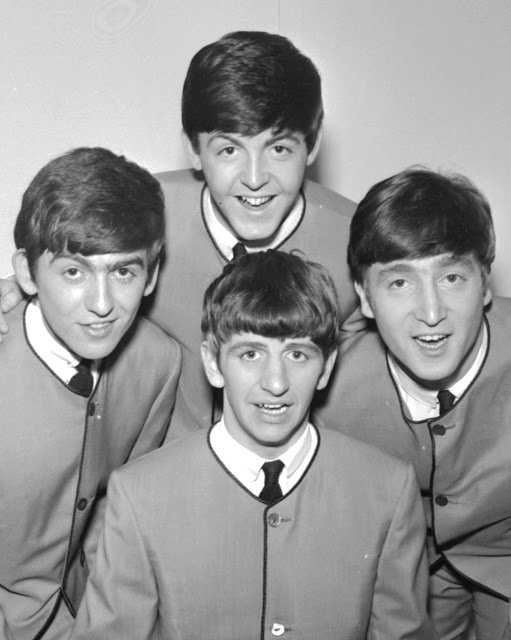

|

| Before. (1963) |

|

| After. (Photo: Iain Macmillan, 1969) |

What fascinates me much more than creating mere harmony together, however, are stellar teams such as these, where the sublimated creative discord itself is their key to success, or at least one of its keys. These are the perversely clever ones, partners such as the bright and shiny Lennon and McCartney and the nearly classically formal Ellington and Strayhorn, who compel our attention so forcefully by the sheer audacity of their genius. The author of Help! carefully classifies the subjects in his book in a manner which helps their legions of fans come to terms with an actually understand the magic, the strange magic, of their joint efforts:

It may seem odd to join together Duke Ellington’s Orchestra and the Beatles in a single study, but the communal tradition (of early African American spirituals) eventually reached both Ellington and them, and each did something special with it. One could say that they brought a composer’s visions to the dynamics of collaboration. What do the Beatles and Ellington’s orchestra have in common? Besides high musical quality, both groups relied on collaboration to an extraordinary degree. Their collective methods were the primary reason for their high quality, which just seems to loom larger and larger as the decades pass. One could even say that they were the two greatest collaborations in musical history.

|

| Working together as one. (Photo: David Redfern) |

Indeed, one could say this, and the author of Help! does say just that. But he also addresses the finer points of public perception and artistic persona in profoundly revealing ways:

Ellington misled the public by exaggerating his own role, keeping collaborators out of sight and off the credits on record labels. Today the situation is much clearer than it used to be, thanks to research on Billy Strayhorn and increasingly honest assessment of the entire phenomenon. To emphasize collaboration runs counter to Ellington’s elite status. Today more value is placed on collaborative creativity than used to be the case, so the time may be right for recognizing Ellington as a genius collaborator. The Beatles, on the other hand, always embraced a communal image. Lennon and McCartney grew so close that they decided to sign their compositions jointly, no matter who wrote what. Deliberate obfuscation about collaboration did not come until after the group broke up, the source being Lennon, who aggressively puffed up his own role. Though he later acknowledged distortions (“I was lying”), his revisionist account was massively influential. Some of the finest writers on the Beatles’ music were misled into thinking that the two principals collaborated as composers only during the early days.

This is a certainty, and although I’m not claiming to be one of those finest writers on their music (my friend the late Kevin Courrier was one of those, in his Beatle book Artificial Paradise) I readily, if embarrassingly, admit that in my chapter on them in Dark Mirror, I was guilty of nearly dismissing McCartney’s genius altogether, though only in comparison to Lennon’s. As Brothers points out clearly, “More than a few found it agreeable to identify the politically aware innovator (Lennon) as the Beatle worth glorifying the most.” Someday I hope to assuage my guilt by writing an entire book on McCartney, probably to be titled The Other Me: The Secret Avant-Garde Music of Paul McCartney, especially in light of the longer and much more diverse compositional career of Paul, some of it concealed by McCartney himself through the use of pseudonyms such as Percy Thrillington and The Fireman, across multiple genres which has come to light in recent years.

In Help!, Brothers clearly illustrates that both Duke Ellington and The Beatles operated at what he called

the nexus of vernacular practice, where creativity from all participants (as per those early black American spirituals), and commercial pop, which required a single-minded focus on compositions that can be filed for copyright purposes. You could say that these groups both shared an ability to impose a compositional vision on collaborative music making. Or to put it in a slightly different way, they each found a way to tap into creative fields opened up by collaboration and to use that resource in the service of compositional definition. What I’m addressing is the relationship designed to promote collective creativity.In the song “Carry That Weight” from their last masterpiece Abbey Road, which McCartney wrote as a sad farewell to his fellow Beatles, he focused on the now obvious fact that

the four individuals would never be able to achieve apart what they had accomplished together. Less poetically, he might have said, Boy, you’re never going to be able to match, by yourself, this harvest we have reaped from vigorously creative interdependence. Duke Ellington understood this fully. His response was to rarely fire anyone from his orchestra and to subsidize their salaries out of his own pocket, doing whatever it took to sustain the most memorable swing band in history. Ellington and the Beatles were unrivalled composer collectives. There are countless examples of this in both jazz and rock. Art music traditionally excludes this kind of flexibility. Ellington and the Beatles aimed not for improvisational spontaneity but crafted compositions. More typically the two realms are kept apart, with specialists staking out their respective territories. What can be achieved by bringing them together?

In this tantalizing regard, the French novelist Marcel Proust often had a uniquely poetic way of expressing something we all might feel or suspect, and perhaps he did so accidentally in this case as well: “The men and women who produce works of genius are not those who live in the most delicate atmosphere, whose conversation is the most brilliant or culture the most extensive, but those who have had the power, ceasing suddenly to live only for themselves, to transform their personality into a sort of mirror.” In the case of both the joint genius Lennon and McCartney and also the mutual muse status of Ellington and Strayhorn, we were blessed with four of the most exemplary mirrors in the history of our shared popular culture.

The author is a Duke University musicologist, but his highly readable approach is decidedly non-academic, a big relief to me, and is aimed at the mainstream lovers of both jazz and pop. In many ways, he demonstrates that jazz was America’s native classical music, and that the highest levels of pop and rock music are Britain’s almost classical forms (with apologies to Elgar, Williams and Delius) and how both evolved from the same black gospel traditions. He merges scholarly analysis with often provocative insights into what makes both music and musicians tick.

And while I’m so busy throwing around accolades about the pairs of composers, I also don’t want us to lost sight (or sound) of the obviously crucial fact that the orchestra, in Duke’s case and the band, in The Beatles’ case, which interprets and delivers so towering an instrumental foundation, were absolutely paramount to their robust success. Ellington knew well the vital importance of his players, cornetist Rex Stuart, saxophonists Harry Carney and Johnny Hodges, among others, in constructing the actual building of his music with Strayhorn. And just as importantly, with an even more amazing alchemy of energy exchange in the case of the breathtaking quartet format of The Beatles, Lennon and McCartney knew full well that their own creative magic was only fully consecrated, so to speak, due to the profound gifts of George Harrison and the vastly underrated genius of Ringo Starr.

Such an observational awareness, of course, expands our appreciation of the magic of collaboration even further, beyond solely the composers, who customarily get the most attention, to the instrumentalist, who contribute to making the actually music happen. Brothers’ book Help!: The Beatles, Duke Ellington and the Magic of Collaboration, explores in wise ways both their brilliant music and the mastery of individually strong egos. His achievement is also that of clarifying both of their undimmed popular successes over the decades since being active on the scene. Most importantly, he shares with us his sensitive comprehension of the mysterious collaborative process itself, which permitted both teams to accomplish a shared aesthetic vision, an achievement clearly much greater than merely the sum of their separate parts.

No comments:

Post a Comment