|

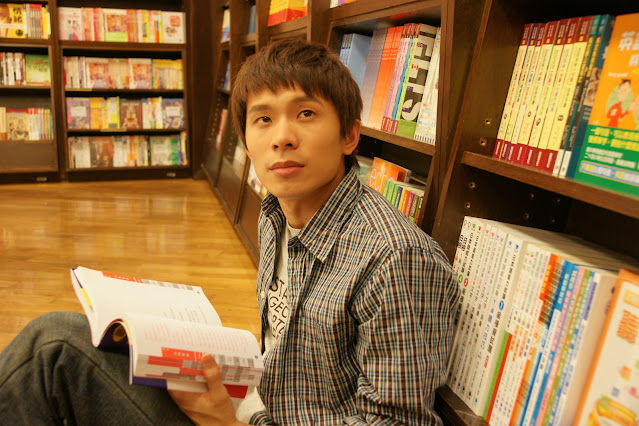

| Chun-Yao Yao in Au Revoir Taipei (Yi Ye Taibei / 一頁台北 2010). |

Writer-director Arvin Chen’s feature debut, Au Revoir Taipei (Yi Ye Taibei / 一頁台北, 2010) – the Mandarin title is a pun on “one night in Taipei” – is a whimsical and slightly farcical romantic comedy that I believe could only have been made in Taiwan, and it’s on YouTube. The key to its tonal success lies in the characterization. It’s my favorite Taiwan film.

In Taiwan, we have this thing we do in social situations: we play dumb instead of taking the initiative, lest we propose something that someone doesn’t want to do, but would go along with anyway just to be polite. The film captures this idea perfectly, which is why it’s one of the few contemporary films to nail a natural-sounding Taiwanese Mandarin. In fact, almost the entire film features characters who don’t know each other very well sharing a scene, and playing dumb describes most of the dialogue.

Kai (Chun-Yao Yao) gets dumped by his girlfriend over the phone from Paris. To prepare to fly over and win her back, he studies a French textbook at a bookstore, where he gets chatted up by Susie (then-starlet Amber Kuo), who works there. Kai’s family can’t fund his trip, so he borrows from Brother Bao (Frankie Kao), a Mafioso who eats at his parents’ noodle stand. But Bao has a condition: he must take a mysterious package with him to Paris. Bao needs this favor because the package’s hiding place is being monitored by the cops (Hsiao-chuan Chang and Jonah Tseng). Playing dumb to his own advantage, Kai agrees. But the plan is overheard by Bao’s protégé, Hong (Lawrence Ko) – an overeager ambitious type with his own Three Stooges-esque lackeys – who spies a shortcut to the top.

The night before his flight, Kai picks up the package with his best friend, Gao (Paul Chiang), who seems more actually dumb than playing dumb – by which I mean simple, straightforward, and content. He’s stupid in the same way one might call one’s beloved dog stupid. They head to a night market for one last meal together, where Kai runs into Susie, eating alone. The Three Stooges show up to try to take the package and, failing that, kidnap Gao instead.

Thus we have our main plotline: the cops chase Kai and Susie, who chase Hong’s lackeys, who are after the package. Most of the excitement comes from the first chase, which passes through the night market, some back alleys, an MRT (metro) station and a city park, across a skywalk, and more. It’s a sneaky way to show the audience an everyday (or -night) side of Taipei that’s not usually on the itinerary. And trust me, a resident of Taipei, when I say that the locations were very carefully chosen.

Most of the dialogue is functional, but the taciturn delivery elevates it beyond mere exposition. Taiwan is a pragmatic place, where actions speak louder than words, and people don’t chat if they don’t really know each other (unlike many Americans, who will famously tell you their whole life story on the bus). Whenever the dialogue threatens to dive below the surface plot, this pragmatism is conveyed with lines such as “Mm” (non-committal affirmation), “Oh” (simple acknowledgment), “Ah?” (seeking confirmation), “What now?” (yielding initiative), and many more ending with “right?” (tentativeness).

What all of this ambiguity and tentativeness does is give the audience space to imagine possible relationships between the characters. Since they rarely say exactly what they’re thinking, the dialogue neither confirms nor denies whatever you’re imagining. You have to wait for a character to take a specific action, and the few points at which one does so are all the more poignant for it.

By a similar logic, the fuzzy dialogue also allows for slapstick, farce, and general absurdity. When you don’t have a fixed idea of what should happen, sudden chance becomes more plausible, and it’s easier for the characters and the audience to just go with it. As they’re chased through the city park, Kai and Susie blend in among a group of middle-aged ladies doing the Lindy Hop, which Susie happens to know and teaches Kai on the spot. Interrogating Gao, Hong’s lackeys learn that they have much in common, and it turns into a conversation, complete with advice about Gao’s (lack of a) love life. During the MRT part of the chase, both the cop and our protagonists obey the metro cop who reminds people that running in the station isn’t allowed. And everyone, across all subplots, watches and laughs at the same trashy TV soap opera, which seems to be having a nighttime marathon.

Every chase must end, but the way that this chases ends may surprise you. Everything about the film feels polished and deliberate; Chen has worked with Edward Yang, and Wim Wenders serves as an executive producer. Chen’s second feature, Mama Boy (Lianai Manbanpai / 戀愛慢半拍), is premiering soon. I can’t wait.

– CJ Sheu has a PhD in contemporary American fiction from National Taiwan

Normal University, in Taipei. He also writes about films and film

reviews on the side, and has been published in Bright Wall/Dark Room and Funscreen (Taiwan). Check out his blog reviewfilmreview.wordpress.com/about, or hit him up on Twitter @cj_sheu.

– CJ Sheu has a PhD in contemporary American fiction from National Taiwan

Normal University, in Taipei. He also writes about films and film

reviews on the side, and has been published in Bright Wall/Dark Room and Funscreen (Taiwan). Check out his blog reviewfilmreview.wordpress.com/about, or hit him up on Twitter @cj_sheu.

No comments:

Post a Comment