“Comedy equals tragedy plus time.” – Dorothy Parker (among others).

“Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.” – George Burns (on his deathbed).

Having previously penned an excellent reappraisal of the consummately eccentric Frank Zappa, unique American composer and creator of the Mothers of Invention rock band, John Corcelli was perhaps ideally situated to undertake this new tome released by Applause Books in which he skillfully explores the similarly exotic outsider status of renegade comedian George Carlin. In his absolutely perfectly titled Outside Looking In: The Seriously Funny Life and Work of George Carlin, he lifts the curtain on the complexities of our mirth, and most importantly for such a delicate mission behind the front lines of laughter, he is sharp enough to appreciate the complex art of stand-up comedy but clever enough to know that it’s much easier to write about it than it is perform it. He leaves that to the experts, while still conducting a master class in how they do what they do. He did, however, study improv at Second City, thus certifying some of his credentials as a keen-minded participant in truly arcane craft.

What’s so funny? It’s kind of a rhetorical question, often aimed at a friend who we may doubt is taking us seriously enough when they smile at some remark we’ve made. But its irony has a double edge. Those two classic quotes above from classy comedic artists pretty much sum up the essence of the mysterious craft of making people laugh so hard that they end up crying. Comedy is serious business, one best left to professionals like George Carlin, the best of whom often proceed through free association without any anticipated customary punchlines at all, often veering perilously close to the edge of truthful tragedy. Keen observers of the human condition in the most serious of ways, they can create a kind of cognitive short circuit using the seemingly silliest of methods, provoking in us the difficulty breathing that separates the good and mildly amusing from the hysterically hilarious. The greatest of them might also become entertaining existential diversions who seem to tell us what we’re already thinking ourselves, deep down. While the loftiest of them all, those such as George Carlin, can become consummate performance artists in an ancient craft of satire that breaks on through to the other side of the brain and initiates a totally new frame of reference. The result: the oxygen deprivation of uncontrollable hilarity, and its close family cousin, tears. That’s the surrealist secret to both satire and parody, one Carlin learned early in life and mined for comedy gold ever after.

The experimental artist Yoko Ono, not exactly known for her witticisms, was inadvertently funny when she observed, “The best way to change the world is simply by being yourself.” It’s all about context. Her remark, seeming to celebrate a stubbornness and rebellion in the face of unfair criticism, was aimed at those who did not understand her personal form of activism, let alone her art or music, but also those who couldn’t deny that she had changed the world somewhat. It was also accidentally sage advice. The experimental comedian George Carlin, as exemplified so deftly in Corcelli’s new book, was a similar master of context and disruption, albeit in a slightly different direction, but in the same domain of counterculture values. As Corcelli’s detailed and entertaining celebration of Carlin’s greatness so clearly illustrates, it was the context of his social place, his time in cultural history and his utterly nonconformist devotion to personal and professional rebellion which allowed him to rise above the average comic and enter a stratosphere of raucous parody reserved for the very few. His personality, an often conflicted mixture of emotional insecurity, literate wisdom and barely suppressed rage, permitted him to fuel a paradoxical desire to disturb and entertain us at the same time. And yes, he too battled the same personal emotional demons as so many other very funny masters of cognitive mayhem.

|

| Lenny Bruce, 1925-1966. |

The masterful postmodern satirist Jon Stewart, an inheritor of much of their impressively literate and scorchingly wacky vibe, once named those he considered to his Holy Trinity of Comedy: Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, and Richard Pryor. Hear, hear. I would add, however, a name that shifts those intricate gag gears into a quartet: George Carlin. And Corcelli’s book goes a long way toward exploring and explaining why Stewart was so, so right in that lofty assessment. For me, his book also reveals the surprisingly intimate close connections between comedy and tragedy that make it both such a mysterious ability and also such a crucial ingredient in surviving our challenging world. Both Freud and Jung designated comedy to be a basic defense mechanism, if not an actual survival mechanism, although from different angles of approach: essentially a variation on the inherent fight or flight response to dangerous situations, in which the comedic mind chooses a third option, stand up and mock. In this regard I’m also reminded of another cogent quote from Carlin (he was loaded with them) which is perhaps even more revealing than he may have intended it to be: “Inside every cynic is a disappointed idealist.” Of course, variations on that theme have also been posited by a myriad of cultural observers, notably Peter Bishop’s version, “Beneath every cynic is a frustrated romantic.”

Both notions work admirably, since both help explain some of Carlin’s acidic assaults on normalcy, and in fact I believe the latter was even used to help explain some of the caustic and often chilly humour of the film director Billy Wilder. Such insights did, of course, arrive much earlier in the classical stages of civilization we inherited from the Greeks and Romans, before they exited stage left while being replaced by the considerably less amusing Catholicism which formed an ingrained rage against authority very early on in the life of the New York Corpus Christi High School student named George Patrick Carlin. Dubbed the “Dean of Counter Culture Comedians,” he arrived on the scene at the perfect time for his hippie-dippy approach to comedy to take root in a culture turning itself inside out with radical change of all sorts, from art and fashion to music and politics. For that reason, Carlin was perhaps an ideal iteration in social satire commentary, one who formed a perfect echo of the sort of upheaval that The Beatles had portended in the pop music world. It was a seismic style shift that would eventually end up in the laconic and surreal hands of comic talents like Robert Klein, Andy Kaufman, Steven Wright and Garry Shandling.

|

| Mort Sahl, 1927-2021. |

The invention of laughter: no one can be credited with creating the spontaneous combustion into chuckles, but the actual serious study of how and why to make people laugh on purpose, well, that has a long and noble lineage, with one of the earliest professors being, of all people, the Greek philosopher Aristotle in his book Poetics, ca. 335 BCE: “Comedy aims at representing men as worse, tragedy as better than they are in actual life.” That is precisely what the Montreal-born Mort Sahl mastered in his deceptively lackadaisical laid-back style of stand-up. I often think he should have been classified as a sit-down rather than a stand-up comedian. Either way, he and his principle student George Carlin both found ways to inject incisive mockery into their albums (remember those things?) and, as analyzed so well by Corcelli, Carlin was able to skewer the two things he hated most in life, hypocrisy and pomposity, with techniques that even the targets of his considerable venom were left roaring at. Until, that is, it clicked: wait, this guy’s making fun of me!

I’m reminded of a certain Stephen Sondheim song from his 1962 musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which was partly inspired by the farces of the Roman playwright Plautus (254 – 184 BCE). Specifically, it was about a certain character named Pseudolus, who daily demonstrated the dilemmas of the dual nature of our existence. That song, "Comedy Tonight," embodied our urge to put off tragedy until tomorrow, in order to enjoy ourselves with a good comedy today, as we remain torn between two lovers: tears and laughter:

Something appealing, something appalling

Something for everyone: a comedy tonight! . . .

No royal curse, no Trojan horse

And a happy ending, of course

Goodness and badness, man in his madness.

This time it all turns out all right!

Tragedy tomorrow, comedy tonight!

Two and a half millennia after the brilliant ancient Greek masters who invented comedy, figures such as Aristophanes, Hermippus, Eupolis and Menander, we’re still in dire need of their instructive medicine. These days, however, as exemplified by our modernist masters during the golden age of comedy – if you’re old enough to remember Jack Benny, George Burns and Bob Hope, that is – we’re still learning to laugh at ourselves and our follies as a means of hopefully restoring our optimism by disposing of our own frequently ominous seriousness. What Carlin added to their mix was a stoned sensibility. He started smoking pot in 1951 at age 14, when the only people who knew what a joint was would have been Black jazz and blues musicians. Life is short, says Carlin’s unique brand of comedy, give yourself a break, you deserve it, so have another drink (or toke, as the case may be).

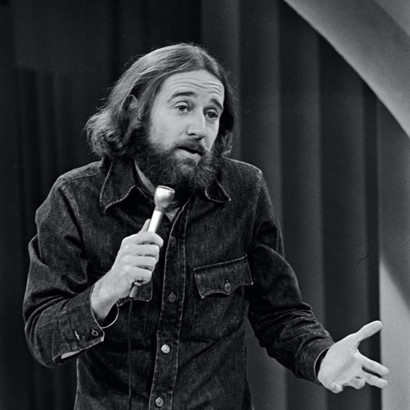

|

| George Carlin, 1937-2008. |

Tragedy plus time. At first glance, that seemingly off-the-cuff and probably tipsy remark made by Dorothy Parker during one of the Round Table discussions at the Algonquin Hotel in New York may have felt like one of her frequently brisk bon mots: “Comedy is tragedy plus time.” But upon closer examination, it just might reveal a deep insight into not just the human condition, but also the theatrical devices we use to embody its paradox in entertainment. The notion that comedy might really only be tragedy viewed from another perspective, that of longevity and experience, also brings to the fore even more perplexing questions about what makes us either laugh or cry together in theatres devoted to watching either live enactments or filmed depictions of human behaviour. Corcelli helps us to understand how and why Carlin skirted so close to sorrowful lament in his sketches, both with early partner Jack Burns (who later partnered with Avery Schreiber, forming one of my favourite comic teams) and later on flying solo. His life was a constant battle against conformity and the suppression of true feelings. But you didn’t have to be stoned to fall onto Carlin’s wavelength. My straitlaced father could hardly contain himself as we chortled at Carlin’s early appearances on the eccentric Ed Sullivan’s variety show, The Tonight Show (with an equivalent master of cool comedy, John Carson, hosting of course), and later, on Carlin’s own HBO comedy specials. Luckily for author Corcelli, even though she was a conservative Catholic lady, his mother seemed to have great tolerance for her second son’s new-found interests, not only allowing him to listen to Carlin’s albums with his elder brother Mike, who introduced him to the comedian’s free association style via Class Clown when John was an innocent 14-year-old, but even allowing herself to surrender to Carlin’s magic listening and laughing in from the kitchen as he extolled the virtues and vagaries of farting, much to her son’s delight. Now there is a mother-son connection to be envied.

The swift repartee of comics like Sahl and Carlin (and their own followers such as inheritors Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert) almost come rattling at you as if they were in a public amphitheatre in Greece itself, where comedy first came into being, which fueled my interest in how Corcelli puts comedy itself on the operating table for an examination in his book. For the purposes of an in-depth dissection, a kind of autopsy of laughter and what provokes it, I turned to an important book from 1965 which I recall being a revealing exploration of this quirky subject. Comedy: Meaning and Form by Robert Corrigan has long fascinated me for the way it so effectively showed us how comedy and laughter are serious business. Indeed, the comedian Steve Martin titled one of his early albums Comedy Isn’t Pretty, and the great comic actor George Burns is said to have left a revealing deathbed remark as his last words: “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.” Carlin hit the paradox right on the head though with his designation of his youthful self, as Class Clown, a mantle he embraced with such glee that it became the title of his fourth comedy recording in 1972, the year he really started being a household name at par with legends like Rodney Dangerfield, Don Rickles and Bob Newhart.

In Corrigan’s book he takes us on a guided tour of an ancient comedic craft, first materializing in Greece’s golden age, again in search of answers to the basic question, “What’s so funny?” by peering into the origins of the invention of comedy, reputed to have been brought into being by the playwright Aristophanes, who live between circa 446 BCE in Athens and 386 BCE in Delphi. He would be among the first creative thinkers to intentionally make fun of an otherwise serious historical figure, Socrates, in a manner that seems to have single-handedly prefigured both the satire and parody that came to be recognized almost two millennia later in the screwball comedies of Hollywood. Prior to that moment, a comedy was simply a tragedy with a happy ending, until it suddenly took centre stage and, along with the famous Greek chorus doing what amounted to their voice-overs, turned to addressing the audience directly in order to evoke jeers in the basic template for what we now call stand-up. Aristophanes, as the father of comedy, used his fearful powers of ridicule to lampoon he philosopher Socrates, and indeed, any other ponderous thinker speculating idly on life’s deeper purpose. Indeed, Plato himself singled out the Aristophanes play The Clouds (423 BCE), origin of the mocking term “cloud-cuckoo-land,” as a form of personal slander, one that contributed in part to the trial and subsequent condemning to death of Socrates.

Thus, laughter is really no laughing matter at all. The comic gesture, what Pirandello called the comic grimace, makes use of the very ludicrousness of comedy to show that life itself is absurd. That was always Carlin’s essential message: am I the only one who notices that modern life makes no sense? I mean, come on! Corcelli masterfully shows us why George Carlin was a truly serious artist whose topical messages often went over our heads because we were laughing so hard. Along the way, the author’s brisk and entertaining narrative outlines how and why, and when and where comedy became so obviously the most effective mirror for our bonkers time in history. He also clarifies the unusual manner in which an inventive attention seeker like Carlin could morph into a highly skilled technician who seamlessly merged two traditional comedic forms, screwball comedy and high comedy, into a single onslaught delivered by a seemingly out-to-lunch weirdo. He was letting us think he was that weirdo; it was the classic persona mask he wore on stage while performing literal vivisection on the contemporary society he so deplored.

|

| Carlin perfected The Shrug as a high art form. |

Further spotlighting the peculiar bond between laughter and tears, Corcelli brings us behind the scenes throughout Carlin’s often complicated life, while always being careful not to psychoanalyze the troubled artist but rather to celebrate the essential genius that emerged at the other end of all his challenging tumult and turmoil. He efficiently divides his bio narrative into four core sections: “Class Clown, 1937-1961”; “Jester, 1962-1970”; “Poet, 1971-1989”; and “Philosopher, 1990-2008.”Along the way, in addition to the key milestones and personal background (including some of the sensitive issues that informed his vulnerable yet powerful persona) we are also treated to mini-bios of the influential figures who inspired his evolving sense of comic self: the daring edginess of Lenny Bruce, the astute urbanity of the great Mort Sahl (who gave Carlin his first solo TV appearance when Sahl was filling in on The Tonight Show in 1962, in between the departure of the mythic Jack Paar and the arrival of the incomparable Johnny); and the incendiary black contemporary counterpart to Carlin’s radical self-revelatory style, Richard Pryor. It’s a wild ride across the most exciting period of entertainment in the 20th century, with frequent rest stops in important parallel zones of intersection: those events, people, places, politics, art, music, film and the shared dreams that made it a century I personally miss every day. But at least we have our own private Aristophanes: his name is Carlin.

Corcelli’s clearly affectionate take on this pop icon shares with us his personal reasons for believing that in addition to being among the greatest stand-up comedians, Carlin was also secretly a poet and philosopher, and a keen observer of the human condition as insightful as Jean-Paul Sartre, but way funnier. His credo was to maintain his youthful status as an irrepressible prankster and turn it into an adult profession, by straining against the strictures of decorum and good taste in pursuit of a singular comic vision. He found it, usually by making fun of serious issues: “Tell people there's an invisible man in the sky who created the universe, and the vast majority of people will believe you. Tell them the paint is wet, and they have to touch it to be sure.” As per that insight of his, George Carlin’s slightly misanthropic view of things was not by any stretch ever inaccurate or false, even when it occasionally tweaked our collective conscience. Perhaps because his humour seemed to emerge from the collective unconscious itself, as Corcelli’s excellent appreciation explains, even those who didn’t like his politics, or his hair, or his language, had to admit that he never lied to them. Especially in the latter years, once television kicked in to launch him right into everyone’s living room, and then once the internet took over from there, propelling him into an avalanche of meme quotes (like the one I just referenced) that penetrated every nook and cranny of a universe where the paint is perpetually still wet.

And since I believe, as I suspect Corcelli does too, that authenticity was the chief cornerstone of what made George Carlin appealing to audiences and so significant to pop culture, I can’t help feeling that the epigram from Carl Jung that Corcelli uses to open his excellent book is also the best one for me to end this appreciative review of it: “The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.”

|

| Carlin in the prime of his prime time. |

No comments:

Post a Comment