|

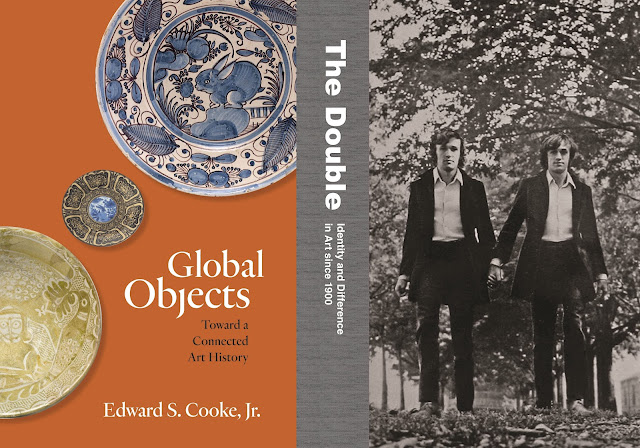

| Princeton University Press (2022); Princeton University Press (2022) |

“We have arrived at an era of humans and their doubles. We no longer need mirrors in order to talk to ourselves.” –Jean-Luc Godard, 1965.

Polarity, duality, dichotomy, opposition, contradiction, mutuality: these art books run the gamut of this spectrum.

As almost always in my case, synchronicity appeared to be at play (in its usual subterranean manner) with the arrival of two remarkably insightful books that explore our binary condition and what lies beyond it, each in its own distinctive way, but both in shared terms of expanding our appreciation for art and cultural artifacts which transcend outmoded definitions of traditional media disciplines and aesthetic values. Global Objects: Towards a Connected Art History, by Edward Cooke, and The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900, by Peter Meyer, are excellent in-depth explorations of how contemporary art provides a mirror of reality, even when that mirror is clouded by myth or fixation. Both are released by Princeton University Press and both approach the polarities of art versus craft and the dichotomies of singular self, with a deft command of their subject matter and theme.

Edward Cooke is the Professor of American Decorative Arts at Yale University and is also the author of Inventing Boston: Design, Production and Consumption, 1680-1720, as well as Making Furniture in Pre-Industrial America in which he argues persuasively for an appreciation of the aesthetic importance of both the so-called ‘decorative arts’ but also handmade culture in all it forms. In Global Objects he extends his reach still further and illustrates how the hegemony of power attributed to ‘fine art’, as distinguished from objects that have a utility in our daily lives, has resulted in a poverty of taste as well as the perpetuation of self-fulfilling prophecies about the importance of the so called ‘sublime’ in the construction of civilizations. Naturally enough, the Eurocentric view of progress in the arts, he explains, has been responsible for relegating other cultures, as well as all the gorgeous objects they produced, to second-, third- or even fourth-tier judgments about their beauty and value.

Equally crucial for this richly illustrated and multi-culturally diverse study of making, in all its forms and functions, is Cooke’s vitally insightful observation about the dangers we face in privileging the ocular-centric and cerebral over the haptic and practical. In other words, our compulsion with intellect over intuition, not just in making, but in everyday living. In excerpts from the book published in his fascinating blog, he stresses “the need for material literacy” in a manner both alluring and self-evident, especially to those of us who are skeptical (if not downright dismayed) at the ever-spiraling influence of the digital and artificial over the analog and the human:

In a time of screen saturation, digitized images of objects and manuscripts, and an emphasis on ‘knowledge workers’ rather than craftspeople, we run the risk of becoming materially illiterate. Increasingly, we have little idea from where materials originate, what they are like to work with, or how they are assembled. Nor do we realize how objects can tell us a great deal about the creative impulses and lived experiences of different times that have not been recorded in written or visual records. When we privilege sight and visual analysis alone, we fail to use a full battery of analytical tools deploying our eyes, touch and embodied experiences to understand the material world.

Cooke further clarifies our dilemma by focusing our attention on certain built-in assumptions that we all grew up learning in our art history studies, especially when the chronological narrative imposed by these studies forces scholars to “string together the examples of a series of artistic centers to construct an evolutionary arc of art history and chart the drift of artistic performance as one moved further away from those centres. As a result, broad comparative strokes have proved difficult to sustain. Part of the difficulty in such a broader approach has been a modern frame of reference: to define art as the fine arts of painting, architecture and sculpture; to assign the highest real and intellectual value to such works of art; and to view the world through filters generated by familiarity with these particular formats.” The simplest way of describing his suggested solutions to our myopia is the author’s recommendation that we adopt what amounts to a horizontal rather than a vertical structure of hierarchies, which allows all kinds of objects made by artists or artisans to have an equal footing in how they carry the embodied meanings of their specific cultures. If it almost sounds like a revolutionary approach to art history, that’s because it is.

The necessity of material literacy informed by cultural curiosity underscores the fact that our field is object-driven and based on collections of objects. We need to pay equal attention to the complementary exercise of theoretical experimentalism to probe possible specific meanings. Examples in this volume provide a kit of tools for future complex constructions of history. In emphasizing a global, horizontal history of the trans-regional world, we build off of and move past vertical regional history driven by nation-states and time period. We ourselves are comfortable living in an interconnected world, so we should use objects to serve as a foundation for an interconnected art history.

Cooke’s way of doing this task, illustrated by hundreds of familiar yet exotic human-made ‘things’, from pots to baskets to furniture, is to examine a broad array of functional aesthetic objects that transcend geographic and temporal boundaries, He avoids traditional binaries such as East versus West, North versus South, and prioritizes flow over stylistic categorizations (and thereby the value judgments customarily attached to them). In short, his masterful attempt to transcend the binary bind of our biases results in an illuminating history of the ‘social lives of objects’, achieved via a deeply human and experienced meaning appreciation which transcends theory altogether.

|

| Edward Cooke Jr., Global Objects. (Princeton University Press) |

Cooke reminds us, “Objects, more than simply reflections of static values, are complex entities that defy easy categorization. They act as active, symbolic agents that emerge in specific contexts and can change in form, use, or value as the move across space and time. Human activity creates material culture, which in turn makes action possible while also recursively shaping and controlling action. Objects mediate social and cultural relations, they become important bearers of memory and meaning. Material literacy is key to acknowledging and understanding this complexity.” And most crucially, this complexity is beyond all those mere binary assumptions about our behaviours as homo-faber: beings who make things.

|

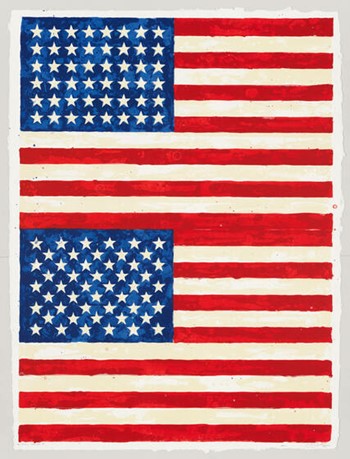

| Jasper Johns, Two Flags (1980). (National Gallery of Art: The Double) |

Meanwhile, as Cooke deconstructs our overly Euro-privileged art history and succeeds in taking our field of vision to more inclusive and diverse zones of non-binary perception, curator James Meyer’s remarkable tome is an elegant exhibition catalogue he conceived for the survey show The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900, which the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where he is the Curator of Modern Art, presented from the summer through the fall of 2022. In it, he confronts the implicit binary structures of our faculties by putting the binary phenomenon of identity, of self and other, under the magnifying glass of modern and contemporary artworks selected for the manner in which they communicate a wholeness which is outside of our inherent tendency to seek the exclusive, the singular: “When two forms or images are presented together, our eyes can’t help but compare them. We see double and identify differences and similarities. The art of the double causes us to see ourselves seeing.” Needless to say, the ability to see ourselves seeing is precisely also what Cooke has asked us to do in his horizontal art history thesis.

In his original review of this exhaustive survey of mirroring, arts writer Sebastian Smee of The Washington Post cheekily and accurately declared: “This all-star show at the National Gallery of Art doubles down on identity. Picasso, Warhol, Duchamp and more big names contribute to an exhibition about duality.” Of course, the popular press, as opposed to art specialist magazines or journals, loves to designate events as “all-star,” but in this case that’s the best way to digest how important a cross-section this really was, especially since those three artists named were, in my estimation, the three most important artists of the 20th century (the fourth being Pollock, who seems to not have depicted duality quite as explicitly as the rest of his cohort). “Identity and Difference also addresses double vision, copies, mirror reversals, shadows, twins and alter-egos. The show is concise, rigorous, funny and heartfelt. As such it’s an antidote to the noxious politics that today turns every word into a watchword against its opposite. Better yet, it’s groaning with great art.” Groaning with great art: I wish I’d written that line. But in sharing an appreciation of splendid and encyclopedic hardcover book of the show, I get to say it again. This book is groaning with great art, and especially with deep ideas about the meaning of that art.

|

| Rashid Johnson, Double Portrait (2008). (National Gallery) |

|

| Seydou Keita, Double Portrait (1995). (National Gallery) |

I’m pleased to reference Smee again in his assessment of the underlying subtext for this thought-provoking exhibition: “Rather than propositions about identity, the works in The Double are mostly expressions of curiosity. Some ask what it means to have two eyes instead of one, or what to make of the fact that our bodies are basically symmetrical—one side mirroring the other. Others address technologies of reproduction which, with every increasing ease, turn one image into a copy of itself, a double.” This last observation, of course, lightly touches upon culture theorist Walter Benjamin’s primary concern over the prevalence of mechanical reproduction of art works, that it inhibits or decays the inherent ritual value of a visual object, thus dissipating its ‘aura’. Yet it is also true, as the didactic panel and label adjacent to René Magritte’s classic 1933 modernist piece The Human Condition, stipulates: “Every picture is a double of what it depicts.” Indeed, every picture also tells a story, and it matters not a jot if the picture is so abstract (such as a Pollock, for instance) that the original natural form that it is abstracted from is not immediately discernible. But it’s there nonetheless, as when Pollock portrays the pure energy of a storm struggling to escape from his canvas. All art, in other words, is mimetic, whether it does so about the real world or merely about our own awareness of it.

|

| René Magritte, The Human Condition (1933). (National Gallery) |

This catalogue is a splendid artifact all on its own, and Kayin Feldman, Director of the National Gallery, is justifiably proud of the print production that captured a signal cultural event commemorating a hugely significant century in the evolution of what art is, what it might be, as well as what it does to and for us: “The art of doubling is an invitation to look more closely, to reflect and consider. As such it reveals as much about us—the identifiers—as it does about the art we see before us. Along with Curator James Meyer’s illuminating introductory essay, six guest contributors help us navigate the concepts and strategies that these contemporary artists--some 90 in number—employ in the creation of their work.” Being a curator, of course, Meyer is slightly more poetic in his approach to clarifying the conceptual framework for his immense speculation on a century of art that often seemed saturated, obsessed even, with elusive questions of identity:

Doubling is a visual grammar involving the combination of forms or motifs that appear alike and unalike. The presentation of shapes, often in a symmetrical format, forces us to compare them. The art of doubling splays and divides vision. Looking at doubled images, we are able to see ourselves seeing. The artists and writers herein challenge essentialist models of selfhood that limit identity, inhibiting our capacity to identify with others and reinforcing difference, thus deepening the divisions among us. We examine the concept of the double in four modes: Seeing Double, a comparison of like with like that invites a perception of likeness and unlikeness; Reversal, a form inverted, mirrored, rotated, turned upside down; Dilemma, a choice between two perceptual or cognitive possibilities; The Divided and Doubled Self, split and shadowed selves, personae, fraternal, romantic and artistic pairs.

The curator of the survey exhibition, and the ostensible author of the major text accompanying it, also clarifies his decision to begin the exploration with the advent of the 20th century, when there is also ample evidence of enough doubling depictions throughout art history to make it an obvious human compulsion and not solely a modern one.

Why begin this narrative in 1900? The reinvention of the academic sketch and copying by modern practitioners; the avant-garde’s embrace of reproducible media such as photography and readymades; Freud’s discovery of the unconscious; and the emergence of geometric abstractions sometime around 1915 are among the conditions of possibility for an art of doubled forms. Any work of imitation is already a double of what it depicts. The dopplegänger (literally ‘double-goer’) is a figure of infinitely varied physical and moral complexion, a shadow that betrays or is betrayed by its owner, a truth telling reflection, portrait, vision: the self-apparition.

Both the splendid exhibition and the important publication of The Double remind us vividly that virtually all art is inherently a self-reflection of its maker and a mirror of the times in which it was made. Along the way, even more vividly we are reminded of Oscar Wilde’s bold pronouncement: “Art is a lie which tells the truth.”

No comments:

Post a Comment