|

| Hachette Books, 2022; Hachette/Back Bay Books, 2021. |

“I never wanted to be a 60’s artist, but to be an artist for all time. If it’s not for all time it’s not worth doing. My mind works in a timeless way. 1966 might as well be 2090—it’s all the same to me.” – Robert Zimmerman

“There’s two things that a man must know in order to get closer to himself, to be a man. One is mathematics, since everything is controlled by numbers; the second thing is money.” – Chuck Berry

These two titanic musical artists were two parallel storms that first ripped across America’s unsuspecting 50’s and 60’s heartland, and then rapidly tore across the whole planet earth with a ferocity only matched by The Beatles. Ironically, the first artist, Chuck Berry, inspired The Beatles, who then were creatively reborn themselves once inspired dramatically by Bob Dylan, along with every other singer-songwriter on the convulsing planet of pop culture. Both from Hachette Books, these books are also an ideal tag team match for taking the full measure of true innovation and influence within their respective fields. In a very real sense, there was popular music before Chuck Berry and then after Berry, just as both folk and rock can only be fully appreciated if assessed both before Dylan and then after his astonishing ascent. RJ Smith’s biography of Chuck Berry, Chuck Berry: An American Life, can rightfully be called the definitive one in a prior flock of works of varying degrees of serious intent: the most serious, the most revealing (often embarrassingly so) and also easily the most readable for both music devotees as well as the general public with a curiosity as to how rock and roll music was born and how it grew into its adulthood as rock. One of his most ardent fans, the equally accomplished pop musician John Lennon, once quipped that if you wanted to give rock and roll another name, you might just call it Chuck Berry. While this is technically true, and quite touching, I’d point out that you could also call it Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Louis Jordan, both of whom were active for a full decade, making the kind of jump rhythm and blues that white folks (most notably the disc jockey Alan Freed in about 1951) eventually called rock and roll. Add into that heady mix Jackie Brenston and Ike Turner and his Rhythm Kings, whose 1951 hit “Rocket 88” was technically the earliest song we can identify as full-blooded rock.

Smith’s book provides us with what came to be popularly known as the Full Monty in another vein, and it sizzles with a full shipment of secrets about the Full Chuck, even though, ironically, what the book most successfully unearths is how Berry managed to maintain a vast distance between not only himself and the public but also between himself and the whole music industry, even including his own musicians. He remains as enigmatic and perplexing a figure as ever, and often a downright disturbing one, a boisterous talent who, in Smith’s words, made it impossible to know what he himself felt about either his performances, his recordings or his vast acclaim. Secretive and strange, yes, and maybe for good reason, as we quickly learn in this gripping narrative, with his agent once remarking on Berry’s absence of any friendly relations with anybody. And yet, the same agent observed, everybody knew him, or at least everybody with a turntable. One of Berry’s lovers summed it up neatly: “Either he was a very complicated man, or else there was no there there. I’m not sure which.”

|

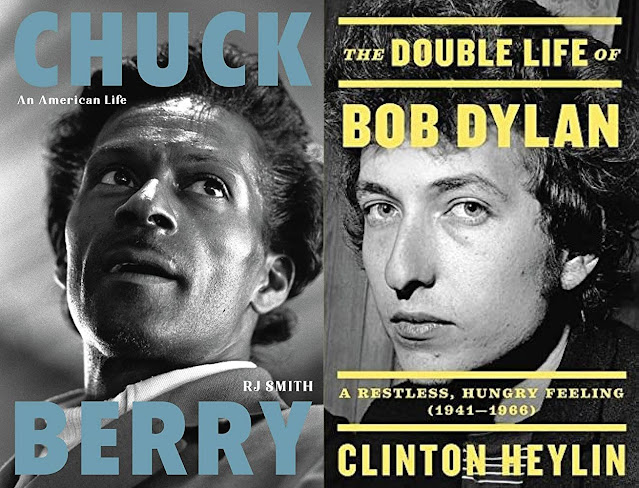

| Berry in 1955, after his breakthrough, “Maybelline” (Wikimedia Commons). |

The book is disconcerting in many parts, but in crucial and important ways that allow us to appreciate the peculiar fact that so often in the arts, especially in music, great things, historically significant things, can be accomplished by individuals with somewhat monstrous characters, sometimes even personality disorders. He came from a rather challenging background. He was born in 1926 to a middle-class family in St. Louis, where, like Ike Turner before him, he achieved early notoriety in the many hopping music clubs in the rough-and-tumble east part of the city. After serving three years in a reformatory for armed robbery. Berry began to take these clubs by storm with his unique brand of saucy and bluesy burlesque antics, and by 1955 the ambitious 29-year-old guitar genius met the man who would alter the course of his life. Muddy Waters was a blues legend and a stalwart at the Chess Records label in Chicago, where he helped the nervy musician score his first recordings, as well as his first million-selling record, “Maybelline,” a tune he constructed on the spot by shifting the melody from an old jumpy country tune by Bob Wills called “Ida Red” and superimposing his Chuck-drenched twitchy energy all over it.

White radio host Alan Freed, who was canny enough to jump onto the bandwagon resulting from a commercial collision course between black rhythm and blues (still called ‘race music’ at the time) and white country/rockabilly, once played “Maybelline” over and over again for two hours straight on his popular Rock and Roll Party program. The national audience, who were just beginning to grasp the fact that rock and roll was a street slang term for sex play, went bonkers for Berry and his unbridled, undiluted sensuality as he twisted and shouted his way through the lament about a bad lady who mistreated her man. Smith is adept at chronicling the musician’s obvious innovations: “He was creating a body of work that would build a musical, rhythmic and lyrical vocabulary for rock and roll. He was a prophet of Black mobility, he was himself in flight, taking Black music to white audiences across the country with a fury.” Indeed, he may well have been the first legitimate, i.e.: financially viable, crossover artist in pop music history. But Smith is also skilled in his sharing of revelations of the darker side of Berry’s antsy behaviour, namely the “often triumphant but sometimes anguished details of his life.”

Although in 1954, the year before Berry’s breakthrough crossover hit, both white stars like Elvis Presley (with “That’s All Right Mama”) and Bill Haley and The Comets (with “Rock Around the Clock”) heralded the nerve-jangling party sound of rock to come, and both became hugely influential, Berry was just getting warmed up by mid-decade. He followed up with “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956), “Rock and Roll Music” (1957) and “Johnny B Goode” (1958). The latter was to be the only rock and roll song included on the Voyager Golden Record sent out into deep space to be discovered by unwitting life forms elsewhere. His ongoing stream of catchy songs seemed to emerge and flow from somewhere deep within the inner space realms of his rather mean-hearted head: “School Days,” “Sweet Little Sixteen” (a distressingly creepy song once you know about his private predilections for young girls), “You Can’t Catch Me,” “Memphis Tennessee,” “Come On,” and the romping rocker “Little Queenie.”

But everything came crashing down around him, almost, as the decade drew to a close, when in December of 1959 he was arrested under the Mann Act after allegations that he had had sexual relations with a 14-year-old Apache waitress, Janice Escalante, whom he had transported across state lines to work as a hat check girl in his club. In 1960 he was convicted, fined $2000 and sentenced to five years in prison. He won an appeal by claiming that the judge was racist, but in his second trial in 1961 he was convicted a second time and received a three-year jail term. A third appeal failed and he did serve one and a half years, until January 1963.

Many commentators have observed the apparent decline of the original rock and roll motifs in the late 50’s and early 60’s, which, of course, was the outer edge of a different sort of pop music, a global brand of rock, just then about to burst forth. Among the sources of the tectonic shift were the retirement of Little Richard to become a preacher in 1957; the departure of Elvis Presley for the U.S. Army in 1958; the public scandal surrounding Jerry Lee Lewis’s marrying his 13-year-old cousin in 1958; the plane-crash deaths of The Big Bopper and Buddy Holly in 1959; the breaking of the payola corruption scandal in the music/radio industry centered on Freed in 1959; Berry’s arrest in 1959; and Eddie Cochran’s car-crash death in 1960. But the biggest seismic quake of all would be the explosion of the British pop invasion, which, coincidentally, took place just about the time when Berry was released from prison, in 1963.

His unexpected return to performing and recording was made surprisingly easier by hot Brit pop stars such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, and their lavish popularizing of his gifts in their own ascent out of the very shadow he had prepared for them. Between 1964 and 1965, Berry released eight singles, among them “No Particular Place to Go,” “You Never Can Tell” and “Nadine.” In 1969, Lennon featured his idol among the line up of his Rock and Roll Revival show in Toronto, Canada, where Berry had to compete with the primal energies of Yoko Ono.

|

| Berry trying to have fun with acolyte John Lennon and Yoko Ono on The Mike Douglas Show, 1972. (Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1972, Lennon would again feature the legend when he and Yoko hosted The Mike Douglas Show for a week. Berry was just as nonplussed with Yoko as he had been a few years before. She, however, was not overly impressed with his legendary status, since her legends were more along the lines of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage. But Berry, was, despite his flaws (and they were numerous and often ominous), an actual legend, and Smith’s excellent biography tells his own private story running in tandem, luckily for us, with the biography of the musical revolution he contributed to so creatively, and with such apparent effortlessness.

Which, of course, is the misleading hallmark of genius, in any artistic discipline: once a genius has done it, it suddenly seems so . . . doable. Berry often seemed to be an alchemist, transforming rhythm and blues into the magical ingredients which made rock and roll, and later rock, so distinctive, with lyrics aimed to appeal to the white male youth market by using graphic descriptions of what mattered most to them in their anxious daily lives: fast girls and fast cars. But his primary, and primal, gift was navigating breathtaking guitar solos and raunchy stagecraft in a blissed-out way that would alter the course of popular music for decades, and still does.

As a singer-songwriter, according to music critic Jon Pareles, Berry invented rock as "a music of teenage wishes fulfilled and good times” (even with cops in pursuit). Berry contributed three things to rock music: an irresistible swagger, a focus on the guitar riff as the primary melodic element and an emphasis on songwriting as storytelling. His records are a rich storehouse of the essential lyrical and musical components of rock and roll. However, in his later years he sustained, through sheer angry willpower, a mere shadow of his own myth, featuring arrests for assault and drug possession, with the massively adored star often descending into self-parody in sloppy sets using under-talented side musicians and sliding into unintentional burlesque with novelty tunes such as “My Ding-A-Ling” (the utterly obnoxious song that made him wealthy beyond measure).

Smith’s bio-saga is a rich one, depicting his rise and fall, and rise again, and then maybe a couple more rises and falls along the way. He never quite explains what Berry’s chief disorder really was, or what made him almost squander a brilliant gift that is bestowed on so few, but then again, no one can. Berry himself touched upon this mystery in his own huge anthem, “Johnny B. Goode”: “He never really learned to read or write so well, / But he could play a guitar just like ringing a bell.” Of all the accolades piled on his guilty shoulders, for me one of the most obliquely revealing came from none other than Bob Dylan: “Chuck Berry was the Shakespeare of rock and roll.”

|

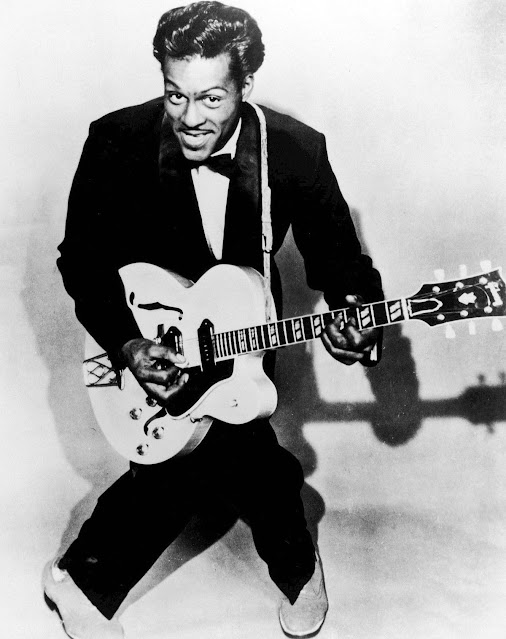

| Dylan slightly the worse for wear at the height of his notoriety, 1966. (Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images) |

When Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, I wasn’t the least bit surprised. The only thing that surprised me was the high number of people who were perplexed by the choice (and the volume of their outcries), with their odd complaint that he was a mere singer and writer of songs. What their bias caused them to neglect to remember, if they ever knew it, was the fact that literature originated as oral delivery, odes frequently sung, long before it was every written down and formalized into the canon we now recognize. At the top of that canon for most people, although I’ve never been a fan of his songs, was Shakespeare. But Dylan was not saying that stylistically Shakespeare and Berry were in any way similar; he was solely remarking on the impact, the influence, the innovation and staying power Berry had in formalizing a whole art form, in his case rock and roll, and how he embodied a crucial borderline of before and after.

Dylan was also admitting, tongue in cheek, that great artists are not always the nicest of guys, just as he himself was often not a nice guy, but that doesn’t alter their stature one jot, as long as they consistently deliver works of either humble poetry like Chuck’s, or the deeper prosody of Bob’s vein, and as long as they don’t murder anyone. And no one is better suited to exploring that gold mine of core human storytelling in songs, the origin of all literature that is our dear, irascible, difficult, yet undeniably authentic doppel-artist Robert Zimmerman, than the obsessively driven biographer Clinton Heylin, author of The Double Life of Bob Dylan. Rolling Stone magazine referred to him as the “world’s authority on all things Dylan,” and that is not at all an exaggeration. Moreover, his new book (his ninth) on the mercurial genius of contemporary song is also worthy of several other accolades. The éminence grise of Dylan scholars, according to Andrew Motion, former poet laureate of the United Kingdom, and a towering forensic analyst of Dylan and his work, as per Will Hodgkinson of The Times UK. Every shade of this worship for Heylin is totally deserved, as is the official designation of his stellar work as both definitive and revelatory.

America has had many, many worthy poet laureates, the current one being Ada Limon, but I’m perplexed as to why Dylan was never awarded this honour, since “Desolation Row” alone deserves that position, not to mention every song on the 1968 John Wesley Harding album. But oh, yes, I forgot, it’s because he’s a popular singer-songwriter, the same lame reason that some offered about his (completely logical) choice for the Nobel Prize.

Elsewhere I have opined about him as our Steinbeck in sunglasses: a novelist named Dylan. In my 2008 book Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, I had a chapter on Mr. Dylan, who, apart from various differing personal tastes, most people can now agree is one of the pre-eminent artists of our era, of several eras in fact. His chapter opened the book for obvious reasons: he had etched the template for what a singer-songwriter in the contemporary age is capable of achieving, assuming that songwriter lives long enough to become an elder statesman of his or her ancient craft, as he has done. The chapter on him was called "The Storyteller: To Be On Your Own," and it encapsulated what, for me, made him not just a pop/rock star but also both a novelist and a poetic island unto himself.

|

| Looking much healthier after surviving into the 21st century. (Photo by David Gahr, 2001) |

So I’m delighted to report that Heylin also realizes, even more expansively than I, that Dylan’s storytelling prowess reflects the ancient origins of all literature, and that every enigmatic song he ever crafted is also a novel capable of embodying the literary essence of Cervantes, Melville and Hemingway: his words tell the tale of the times we live in. In the case of Heylin’s esteemed chronicle of Dylan’s mastery, and again reflecting why The New York Times once called him “the only Dylanologist worth reading,” his prior eight approaches to this subject do not diminish over time but rather come into clearer focus in the context of The Double Life. The first volume of a projected two or three future forays concentrates on what he calls “a restless hungry feeling,” the ideal way to portray the Dylan period from 1941 to 1966. His earlier outing, Dylan: Behind the Shades, remains in print over two decades after its release, along with two volumes relating the backstory to over 600 original Dylan song and Revolution in the Air, Still On the Road, Stolen Moments: Dylan Day by Day, and The Recording Sessions, 1960-1994. Luckily, Heylin has even covered Dylan’s wonky religious phase, Trouble in Mind: The Gospel Years of Bob Dylan, so I don’t have to.

So then, what exactly remains to be said about this creative titan? Plenty, as it turns out, and Heylin says it like no one else could. There might be many listeners and authors as fanatical about Dylan than I am, even moreso, but few, if any, have the acumen and powers of interpretation to do what Heylin has done with this new epistle to the faithful. I take may hat off to him as the master of this domain. And the key authorial turning point was when Dylan turned over a boatload of 6,000 pieces of archival material (including lyric manuscripts, notebooks, photographs, letters and audio/visual material) never before seen, read or heard by the public, let alone chroniclers such as Heylin. Imagine: Heylin had access to complete session tapes from Dylan’s catalogue, as well as the raw footage from various film documentaries on the artist. He shares with us granular details about Bob becoming Bob and then Bob being Bob, in two major episodes: “A Thief of Thoughts,” covering 1961-63, and “A Thief of Fire,” covering 1964-66, when Dylan withdraws from the spectacle of being himself (much the way Lennon broke down under the weight of his own legend).

Heylin himself best describes the archival dam bursting open:

So much has been revealed in the two decades since I last tried to frame Dylan’s life between hardback covers. As a popular poet once said, everything passes, everything changes, and one March day in 2016 the world of Dylan studies spit open and a great gaping hole at the heart of master’s art was filled, if not to the brim, certainly well past the half-full glass of the most optimistic Dylan scholar. Bob Dylan’s Secret Archive was the first breach in a veil of secrecy cast over a clandestine excavation of Dylan’s personal archives. ‘Twas The Hitler Diaries revisited, with one important difference: this archive was for real. The “Tulsa Archives,” all of these I thoroughly trawled. Suffice to say that even though Dylan banked a $22 million cheque, he has retained copyright on all the material, which means a degree of keeping in control with his character has been retained. The Double Life aims to tell the life and times of America’s most important twentieth-century popular artist, a new kind of biography written in the same milieu as its subject but with the kind of access to the working processes usually possible only after an artist’s death. A cohesive portrait akin to when some Renaissance masterpiece is restored to its truer self—recognizably the same figure but sharper in detail, the colours more illuminated.

Wow, I have no problem readily admitting that Heylin has written in that brief intro excerpt his own book review, and it’s an utterly honest one too, that many of us I’m sure are reading while humming the melody from that blissfully self-aware song of Dylan’s, “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” recorded by The Band in 1971. Herewith an excerpt:

Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You could almost think that you're seein; double

On a cold, dark night on the Spanish Stairs . . .Yes, it sure has been a long, hard climb

Newspapermen eating candy

Train wheels runnin’ through the back of my memory

When I ran on the hilltop following a pack of wild geese

Someday, everything is gonna be smooth like a rhapsody

When I paint my masterpiece . . .

Had to be held down by big police

Someday, everything is gonna be diff’rent

When I paint my masterpiece.

Clinton Heylin not only does a great service to popular cultural heritage here with the first volume of his newly renovated and expanded Dylan saga; he also puts the precious painting in a brand new frame, suitably gilt-edged and worthy of the active renaissance of both folk and rock music that Dylan truly represents. Because if Chuck Berry was the Shakespeare of rock and roll, then Bob Dylan is the John Steinbeck of rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment