|

| Lucien Clergue, Portrait (1956). |

“Mystery is the essential ingredient of every work of art.” – Luis Buñuel

Who and what do we see when we study the splendid photographic portrait of Pablo Ruiz Picasso captured by the esteemed Lucien Clergue in1956, when the Spanish artist was at the height of his powers? Having been adopted as a global cultural citizen beyond all mere geographical borders, the words who and what are both applicable in his unique case, as someone who was as vital and revolutionary in painting as his countryman Cervantes was in literature three hundred years earlier. So when Clergue memorialized that dramatic face, some four decades after the artist first reinvented the history of art at the turn of the last century, recasting it in his own image by collaborating with Georges Braque in the revelation of Cubism, and with roughly another two tumultuous decades still remaining in his titanic aesthetic mission, what sort of portrait telegram did the photographer manage to send us all in the future, and yet further into the future of the future? His portrait seems to whisper: behold, a living archetype.

Picasso’s elusive and mercurial character, a persona he appeared to perform as if he lived on a stage, still has the capacity to allure and amaze us. With good reason, and these powerful works on paper assembled here are an accurate indication of exactly why. He was a towering figure who looms large in both the art world and the world of popular culture, a gargantuan artist beyond most limits and even any definitions. Gazing at the overwhelming confidence in the awesome face of the man behind these prints, I am often reminded of the words of a favourite Brazilian author, Clarice Lispector: “He had the elongated skull of a born rebel.” I do hope so, Clarice, but all the landforms of his skull grew inward, like stalagmites, rather than upward and out. His Guernica painting from 1937 was one such interior landform, but then, so are his many masterful prints: each one is a mountain peak in reverse on paper, a spritely graphic Everest.

Firstly, and most obviously, Clergue’s portrait was the image of a man of supreme confidence, but it was also the picture of an artist of such self-assurance that he somehow knew that his place in the history of art would certainly align him with past giants in this procession of powerful agents of change: Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, Picasso. And like them, he is quite rightly just as acclaimed as a maker of art prints in multiple media as his forbearers also were, and for creating a seemingly endless supply of new ways to transfer images from a template onto another surface, usually paper or fabric. With a singular matrix fabricated out of wood, metal, glass or stone, and using ancient tools and chemicals to carve and bend the inert surface to his will, like his predecessors a printmaker such as Picasso dazzled us in a medium parallel to (but not beneath) painting itself, out of which he incised primal visual reveries in woodcuts, engravings, intaglio, etchings, linocuts, lithographs and beyond. Of his peers, only Dali created as many graphic images, but with considerably less artistic acumen.

This alchemical process also incidentally produces a ghost of its own creation, enabling the artist to make more than one image of his mark-making, although usually limiting the imprints to a significant and rare edition number. The duplication of multiple images, sometimes with either minute or major alterations made to their depth, colour and tonality, immediately threw down a gauntlet to the one-of-a-kind and aura-laden ritual nature of painting as a romanticized form of iconic transmutation, a singularity. Picasso changed all that forever, just as Dürer, Rembrandt and Goya had done, especially his fellow Spaniard Goya in his late black works. Like them, this superlative painter was so ambitious in his aims that perfecting his radical experiments solely in paint was not nearly enough to satisfy him. He had to branch out, first into multiple print imagery in two dimensions, and then eventually into the realm of three dimensions, using ceramics and sculpture. Gaze at and into enough Picasso prints and they eventually take on the significance of spiritual icons, but often evoking the most carnal of churches.

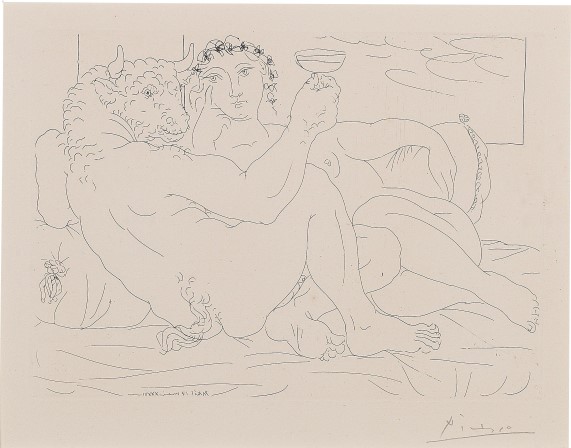

|

| Minotaure (1933). |

In fact, his immense passion was such that these graphic works remain as fresh today as the day they were fabricated: thus his work really does provide a way of fixing the memory in place, not always securely, perhaps, but always surely. It was in his magical prints, so deceptively simple that often viewers mistake them for mere drawings (another medium in which he not only excelled by transformed the rules of the game forever) that he proved himself to be the godfather of the three other most important and influential artists of the 20th century: Duchamp, Pollock and Warhol (another master of multiple prints, in his silkscreens of both allure and audacity). Now, yes, as a historian, I hasten to point out that there were a host of other important artists in the last century, and yes, many of them women. However, it was these four who occupied a special place of honour, reserved for those who alter a terrain so decisively that all who came afterward had to contend with and comment upon their influence. This is exactly the disconcerting sensation that critic Harold Bloom astutely referred to as “the anxiety of influence.” And nobody provoked it more severely, and for a longer duration of celebrity, than Picasso, not only in his brilliant paintings over a succession of periods, styles and eras (including even the pop art era) but perhaps especially in his non-painterly extensions of drawings and graphic prints.

How he managed to accomplish this feat still remains something of a mystery, although we can find solace in his fellow Spaniard, the innovative filmmaker Luis Buñuel, when he reassures us that this nebulous quality, the ineffable writ large, as it were, is precisely what most attracts us to worship at the aesthetic altar of certain sublime works of art. And although it took time for him to accomplish, just as it took time for the radical Impressionists (his only historical counterparts apart from those more ancient artistic relatives) to be recognized as what they truly were: the future, embodied right in front of a trembling past and present, Picasso did so during his own lifetime. For an art historian and obsessive lover of painting, the opportunity to write about Picasso is almost as exciting as the chance to have seen so many of his creations across the dizzying decades of the modernist era. In fact, as art historian David Sylvester has cannily reminded us, evocations of previous art, including his own, is a constantly conspicuous feature of Picasso’s ongoing oeuvre. Indeed, Sylvester once ironically quipped: Picasso might almost have been aiming to ensure full employment for his posterity’s art historians, all of us scriveners in other words.

In his finest work, Sylvester suggested, there is always a dialogue with all art history itself, and a charming complicity between him and himself, between himself as both artist and as audience. I would go even further and claim that his conversation was not only with all the artists in past history, with Dürer, Rembrandt and Goya, let’s say, but even with all the artists in the future whom he was boldly spooking into daring to make art after his passing in 1973. By this I mean to say, quite literally, that Picasso was answering history while also simultaneously asking posterity. What was his question for the future? I’d wager it was something along the lines of: “I did THIS! Now, you do SOMETHING ELSE.” His targets? Some known to him, like fellow epoch-carving contemporaries such as Duchamp (who, like Picasso, eventually turned his own life into a work of art); Pollock (who, like Pablo, was out there enough to declare that he WAS nature itself); and Andy, perhaps my favourite of all futurologists (who forced even the cleverest among us to go back and reread all the works of Walter Benjamin, for instance). Others he only admired from a temporal distance, such as Goya (whose exemplary grasp of the vagaries of the human heart echoed his own).

|

| Minotaure (1933). |

Picasso consistently re-examines and re-explains the human gaze like no one else before or since. And what still keeps contemporary artists up at night, when not experiencing nightmares about the Spaniard’s apparently effortless virtuosity in child-like print dreams forced onto paper by his own worker’s hands? He was that rare artistic genius who actually thought with his hands. And his narrative is still just as startling today as it was after his earliest Neoclassical bathers-motif constellations, as it surged forward with the Vollard Suite of images in the 30’s. The true shock to our retinas was his rebellious return to the human figure again, after having dreamed up Cubism and proto-abstraction with his peer Braque about twenty-five years earlier. He then triumphantly managed to make over 1,000 prints for us to decipher at our leisure, a leisure he never allowed himself to have.

Some of them are included in the carefully curated selection provided by the Odon Wager Gallery. Onward he soldiered and ever more boldly he experimented: through the eroticism of the Le Viol series, with its abrupt retrospective of the most severe of all classical and mythological motifs, that of romantic love as an exotic kind of combat; and his Rembrandt series, a feedback loop embodying some of his wildest projections. He then took time off from the tempest to recharge his batteries via his tender Sculpture Studio series. His brutally simple bullring escapades, however, peel back his subconscious for all the world to behold; and his harrowingly Freudian Minotaur series, especially the dying minotaur theme mashing bullfighting and mythology together, still deserves to be called his finest work in the multiple domain of printmaking.

We savour his love-drenched portraits of various favourite lovers and models such as Dora Maar in the 30’s, which shared the aura of romance in his lived life, no matter how self-centred it often became. Then my personal choice as his best era, decade, and epoch, the 40’s, during which he laid bare the full geometry of his desires, all of them, with his enigmatic nudes in raw space (seated or with knee raised). It was ten years before Clergue’s mesmerizing portrait of the artist that Picasso created what I have long believed was one of the greatest prints ever produced by anyone anytime, Portrait of Françoise Gilot, in 1946, now enshrined in the Museum of Modern Art. That period is also represented well here by the equally mesmerizing Femme au Fauteuil of ’48, yet another glistening and recursive evocation of the divine muse motif that perpetually haunted this artist. La Répétition, printed decades later, still commands our rapt attention for its tacit acknowledgement that we are all of us wearing masks in a communal play, and none more dynamically than Mr. P, whose every single work was literally a frothing meditation on persona.

|

| Picasso at play, a crucial part of everyday life. |

Closer to our own time, Banderilles (1960) somehow manages to relieve the bullring of some of its sublimated and stylized brutality by rendering reality as a defiant dance of thanatos with its tango partner, eros, a stunning example of the stark boldness of his black and white sensibilities. While Profil d’Homer Barbu (1963) shares some of the cartoon qualities of both the then emerging Warhol and Lichtenstein, at first, until we remember that the kartone was a medieval drawn depiction of a preliminary design for a later finished artwork, used most notably by Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael. And it was used with equal impact by Pablo, Andy and Roy, with the important distinction that, for them, it was the finished work. Revolutionary Cart in Motion (1968) is an ideal example of that other personal perspective of his: celebrating relocation writ large, as if it was Picasso himself who was repositioning the modernist agenda according to his own creative whims. And yes, he was.

Restless and protean, a force of both nature and culture: these are the most accurate descriptors for the poetic visual genius of Picasso, a figure who revolutionized the art of painting to the same degree that Caravaggio did at the outset of the Baroque era. To some of us, Picasso’s works, partially pictorial, partially abstract, and totally expressionistic in their private compulsions shared publicly, were in fact almost a harbinger of the Neo-Baroque. His works share the same overwhelming immersive and multi-sensorial aspects of that style, albeit generated and delivered in quite a different visual wavelength, that embodied what the poet Octavio Paz once called The Labyrinth of Solitude. While Paz was referring to the creative friction between two cultures, in Picasso, and especially in his alluring prints, we witness the creative friction between two times: the past and the future. Both a mythical presence and a real person at the same time, he was not just Theseus himself, forever searching for a thread to lead him out of the labyrinth, or the raunchy Minotaur itself, keeping himself pleasured in a playground of his own making; he was also the Labyrinth itself, with all of us wandering through the twists and turns of his own shared dreams. Luckily for us, he himself was also the aesthetic thread leading us all out of that amazing maze. Perhaps the Maestro himself summed it up most succinctly: “If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.”

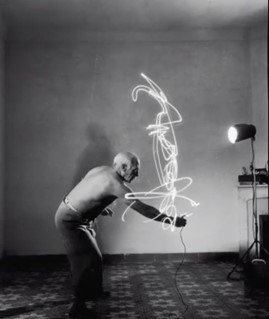

|

| Picasso drawing a Minotaur with light. |

No comments:

Post a Comment