|

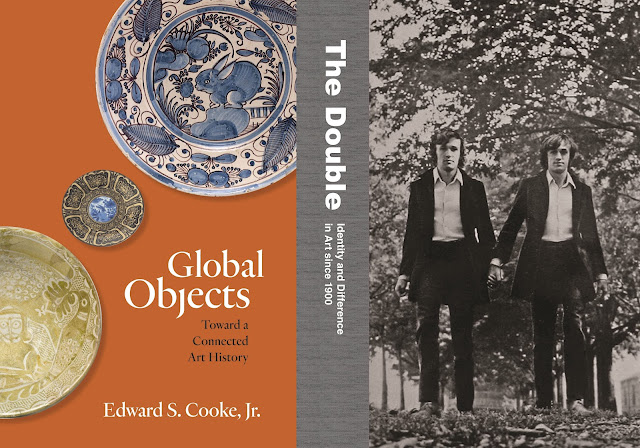

| Annaleigh Ashford and Josh Groban in Sweeney Todd. |

Despite the intermittently brilliant Stephen Sondheim score and a superb cast headed by Len Cariou and an unforgettable Angela Lansbury, I had a medium cool experience with the original 1979 Broadway production of Sweeney Todd. It felt inflated, overproduced (a response I have had to a few other Prince shows), and determined to make a statement competitive with that of Brecht and Weill’s The Threepenny Opera, which was the obvious inspiration for Sondheim, book writer Hugh Wheeler and Prince. But the material, a grisly horror derived from Christopher Bond’s 1973 rewrite of a mid-Victorian melodrama, is thin. At the end of the first act, thinking he’s missed his chance to murder the corrupt Judge Turpin, who trumped up a charge against him and had him transported so he could get his mitts on Sweeney’s innocent wife Lucy, Sweeney, “the demon barber of Fleet Street,” sings “Epiphany,” in which he decides that he’s going to visit his frustrated revenge on his customers because “they all deserve to die.” And Mrs. Lovett, his landlady, who runs a pathetic pie shop with the only stringy meat she can afford, comes up with the scheme of using the corpses to make her wares sweeter and juicier. Todd loves the idea, so they become business partners. In the first-act finale, “A Little Priest,” he argues that since society is built on men devouring each other, he and Mrs. Lovett might as well make the metaphor literal. “A Little Priest” is a wonderful burlesque-style novelty number constructed on a series of increasingly funny puns about their imagined victims. But it’s not exactly “The Second Threepenny Finale” (“What keeps a man alive? He lives on others”). Sweeney Todd is a cleverly devised penny dreadful, not a social satire.

What turned me around about the musical was the 2005 Broadway revival, directed by John Doyle, which had begun life in the West End. Starring Michael Cerveris as Sweeney and Patti LuPone as Mrs. Lovett, it was leaner and tighter than the original, with ingenious Brechtian effects – and it made no attempt to sell itself as profound social commentary. The new Sweeney Todd, directed by Thomas Kail, with musical direction by Alec Lacamoire – both Hamilton alumni – is almost as good as Doyle’s. And it has an even better Mrs. Lovett than LuPone, Annaleigh Ashford, whom I loved in Dogfight and the 2014 revival of You Can’t Take It with You (with James Earl Jones) and the 2017 revival of Sunday in the Park with George (where she played opposite Jake Gyllenhaal). She’s amazing. Slighter and more kinetic than her predecessors, Ashford looks like a devilish rag doll, and every physical choice she makes – and many of her vocal ones (like switching keys twice in the middle of her show-stopping first song, “The Worst Pies in London”) – is inspired. When she played this role Lansbury embodied the play’s music-hall origins, while LuPone’s numbers were like Brecht and Weill done as punk rock. Ashford is lighter on her feet and loonier, and her performance harks back to revue comedy – specifically to Imogene Coca, who partnered Sid Caesar so sublimely in the live TV days.